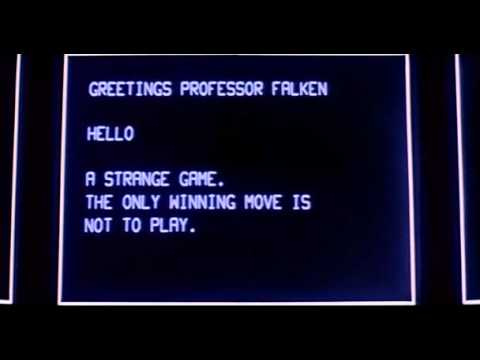

Title 42, or when the only winning move is not to play

(DOJ is going to have to play.)

When Covid struck in March 2020, the Trump Administration issued its so-called “Title 42 order.” In the name of stemming Covid, the Title 42 order prevented would-be asylum applicants from crossing the Mexican border into the United States.

The Biden Administration has since decided that the Title 42 order is no longer necessary, and in November 2022 a federal court decided it was illegal and vacated it. But on December 27, 2022, the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 vote, stayed that district court order. As a result, the Title 42 order remains in effect. The Supreme Court also granted certiorari to decide whether a coalition of states, led by Arizona, waited too long to file a motion to intervene in the case. The case is called Arizona v. Mayorkas. Oral argument is scheduled for March 1, 2023.

Erwin Chemerinsky thinks the Supreme Court’s order “can only be understood as five conservative justices advancing a conservative political agenda, in violation of clear legal rules.” He is wrong.

In this post, I will try to do two things. First, I will explain what is really going on this case, and how the case illustrates many of the pathologies of modern day administrative law litigation. Second, I will show that, contra Professor Chemerinsky, the Justices were not violating “clear legal rules” in support of a “conservative political agenda.” It is always a better idea to try to figure out why the Justices did what they did rather than accuse them of bad faith! Actually, what happened here is that the Supreme Court had no “clear legal rules” to apply. Instead, by virtue of certain unique characteristics of the Supreme Court, the Court was applying highly discretionary legal standards—so discretionary, in fact, that no neutral principles exist that would assist the Court in applying them. Given that extreme degree of discretion, it is no surprise that there were five votes to close the border. If one is upset with the Supreme Court’s order, the fault lies not with the Justices, but with the standards they were asked to apply.

Let’s take a closer look.

Whatever you do, we’ll sue.

Under 42 U.S.C. § 265, the CDC has the power to “prohibit” “the introduction of persons” into the United States in order to prevent the “introduction” of a “communicable disease.” In March 2020, in response to Covid, the Trump Administration’s CDC invoked Title 42 and closed the Mexican border, with exceptions for citizens, permanent residents, and some others. As a practical matter, this meant that asylum applicants could no longer cross the border.

In August 2021, the Biden Administration’s CDC decided that Covid was still a problem and the Title 42 order was still necessary. In April 2022, the CDC decided that Covid was waning and the Title 42 order was no longer necessary, so it lifted the order.

This all sounds normal and reasonable. But because this is America, both sides sued. One group of plaintiffs (states with Republican AGs) sued in the Western District of Louisiana, where 100% of the active judges are Republican appointees, alleging that the April 2022 order lifting the border closure was illegal. Another group of plaintiffs (immigrants seeking asylum and their families) sued in the District of Columbia, where most of the judges are Democratic appointees, alleging that the March 2020 / August 2021 orders closing the border were illegal.

And, because this is America, both sides won.

The Biden Always Loses Doctrine (“BALD”)

Let’s start with the Republican AGs’ suit. In May 2022, a month after the government announced it was lifting the Title 42 order, Republican AGs persuaded a federal judge in the Western District of Louisiana to grant an injunction forcing the government to keep the Title 42 order in place.

It may seem weird to the unstudied observer that a federal judge would ban the government from opening the border, 3 years after Covid began. However, this outcome was predictable. Experience has taught that if the Biden Administration does anything remotely controversial related to immigration, then Republican AGs will challenge that thing, usually in Texas but sometimes in Louisiana, and the Biden administration will lose. Some of these decisions are reasonable, others are not, but the outcome is always the same. Appealing those orders does no good, because appeals from Texas and Louisiana go to the Fifth Circuit, where the Biden Administration always loses as well. This is undoubtedly frustrating to the earnest civil servants crafting these policies and the earnest lawyers going down to Texas and Louisiana to defend them. However, this is simply an unavoidable reality that the Biden Administration has to manage, and one needs to understand this reality to make sense of the government’s tactical decisions.

I don’t mean to pick on Republican-appointed judges. There are Democratic-appointed judges who were equally enthusiastic about enjoining the Trump Administration’s work product. However, Republican administrations have the luxury of a Supreme Court that is willing to issue shadow-docket thunderbolts wiping those injunctions out. That luxury is not available to the Biden Administration, so in crafting its strategy it has to think a little harder.

In this particular case, the Western District of Louisiana ruled that the April 2022 order was unlawful because the Biden Administration did not engage in notice-and-comment rulemaking. In the view of the Western District of Louisiana, the CDC should have promulgated a notice announcing its tentative thinking that maybe, Covid isn’t as bad as it used to be. It should have then solicited the views of public commenters, who would have consisted of a mix of (1) extreme Covid hawks going on about the latest new variants detected in waste-water and (2) anti-immigration types raging about the caravans. After pretending to take these comments seriously, the CDC should then have reaffirmed that yes, we still think Covid isn’t as bad as it used to be. The CDC said that it had good cause to forego notice-and-comment rulemaking, and (in my view) it was clearly right on this, but this argument was never going to overcome the BALD.

Why didn’t the government engage in notice-and-comment rulemaking? Was it lazy? No, it’s because of the BALD. If the CDC had gone through notice-and-comment rulemaking, then Republican AGs would have sued the CDC anyway and prevailed. The district court would have ruled that the CDC didn’t adequately respond to a comment, or it didn’t consider alternatives, or its decision was pretextual and the it was never really going to change its mind, or something. This would have wasted several months and left the government no better off.

Another solution was needed.

Enter Huisha-Huisha

While it was defending the lawsuit in Louisiana, the Biden Administration was defending another lawsuit in D.C., alleging that the Title 42 order itself was illegal. In November 2022, the plaintiffs in that lawsuit won too.

The D.C. court’s decision had the effect of, as a practical matter, mooting the Louisiana court’s decision. Can you see why? The Louisiana court blocked the repeal order. So the original Title 42 order remained on the books. But now the D.C. court blocked the original order. So now neither of them are on the books. It’s as if Covid never happened.

Why did the D.C. court do this? The centerpiece of its decision was its conclusion that the Title 42 order was an unexplained departure from the CDC’s pre-Covid views. So, … working through this … the CDC was banned by the Louisiana court from opening the borders because the CDC didn’t think hard enough about whether, from a Covid perspective, 2022 was different from 2021. But the CDC was also banned by the D.C. court from closing the borders because the CDC didn’t adequately explain why it thought the post-Covid world was different from the pre-Covid world. So the CDC didn’t do anything right, and so we will treat the CDC has having done nothing. I have my issues with the CDC, but it is hard not to feel bad for the CDC.

The D.C. court also gave lots of reasons why the CDC’s order didn’t make sense (“arbitrary and capricious” in administrative law-speak), such as that the order covered 0.1% of land travelers and served no useful purpose in stamping out Covid. This portion of the court’s opinion is quite persuasive, and is reminiscent of Judge Mizelle’s order enjoining the mask mandate on airplanes, trains, and busses, which famously caused passengers to rip off their masks in mid-flight and made Judge Mizelle a Republican hero. In any other context, Republican AGs would have been delighted by a ruling that the Biden CDC’s efforts to stamp out Covid were useless, but consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

This order left the government in a strange position. Should it appeal? On the one hand, it usually appeals when it loses big cases, and perhaps it took umbrage at the district judge declaring that the Biden CDC was irrational. On the other hand, it didn’t actually want the Title 42 order to exist.

So it took a skim milk approach to fighting the order, appealing it but not asking for a stay pending appeal. This means that the parties would file their briefs in leisurely fashion, while the Title 42 order was not being enforced. So … I guess the government was envisioning a scenario in which it “prevails” in the appeal in 2024 or 2025, following which the border would be re-closed to asylum applicants, on the theory that closing the border actually did make sense after all in 2021? Probably not, this would be a ridiculous outcome. Probably the government was hoping that the Louisiana court’s ban on lifting the Title 42 order would be overturned one way or another while the appeal was still pending. And then the D.C. Circuit could vacate the district court’s order and remand for dismissal as moot, and the government could get the best of both worlds: no Huisha-Huisha decision but also no Title 42 order.

The Republican AGs, of course, recognized what the government was trying to do. So after two years claiming that CDC was a malign force seeking to destroy freedom, the Republican AGs immediately went to the D.C. Circuit and asked to intervene in the litigation. They claimed that asylum applicants imposed costs on them, and so they should be able to defend the CDC’s honor and seek a stay that the CDC itself did not want.

No, said the D.C. Circuit. According to the D.C. Circuit, this motion was filed too late. The D.C. Circuit thought that the Republican AGs should have predicted, months earlier, that the government wouldn’t seek a stay, and should have sought to intervene then. The Republican AGs’ blunder, according to the D.C. Circuit, was waiting until the government’s predictable decision to not seek a stay actually materialized.

So, we all know what happened next. The Republican AGs moved the Supreme Court for an emergency stay of the DC court’s decision (that is, the decision enjoining the Title 42 order). The Supreme Court granted the stay, granted certiorari on whether the D.C. Circuit should have allowed the Republican AGs to intervene, and set the case for oral argument on an expedited schedule.

Hold the phone.

Why is the Supreme Court granting certiorari on the seemingly random question of whether Arizona should have moved to intervene in April 2022 rather than November 2022?

Well, as you may have noticed, we now have a 6-3 majority of Republican appointees on the Supreme Court, who are doing things such as overturning Roe v. Wade. In many cases, once the Supreme Court has granted certiorari, it is already over. If the Supreme Court grants certiorari to decide whether a Christian website designer has to make websites for same-sex couples, the Supreme Court is going to decide that the Christian website designer does not have to make websites for same-sex couples.

(Actually, some cases are suspenseful, but that’s because the legal Overton window has moved. For example, I think the Supreme Court is likely to reverse the Fifth Circuit’s decision holding that people subject to domestic violence restraining orders have a Second Amendment right to possess firearms (!!). But it’s a suspenseful case, whereas a few years ago it would have been obvious that the Supreme Court would reverse. By contrast, the type of case that was suspenseful when Justice Kennedy was the swing vote, is not suspenseful anymore.)

Although the Supreme Court is a powerful court, it cannot generate cases out of thin air. The Court only hears cases that litigants ask it to hear. And so, in lots of cases, the only way to win is to not play—that is, to not ask the Supreme Court to hear a case.

But litigants who lose in lower courts are the ones who petition the Supreme Court to hear their cases. Maybe a lower-court winner wants to avoid Supreme Court review, but why would a lower-court loser want this outcome? Don’t people dislike losing?

Usually they do. But there is one type of case in which they are happy to lose: when they are defending something passed by the other political party. Typically this happens in two situations: (1) When a Democratic AG is defending a law enacted by a Republican legislature or vice versa, and (2) When a Democratic AG is defending the administrative action of a prior Republican administration or vice versa. (This case technically falls into neither category because the Biden administration initially re-upped the Title 42 order, but the Title 42 order’s soul lies in the Trump administration.)

And so, when you have Democratic AGs charged with “defending” laws or policies they want to get rid of, their winning strategy is to lose in a Democratic-friendly lower court and not appeal. Of course their Republican counterparts realize this and try to intervene and defend the laws or policies they like. Everyone knows that if the Republican counterparts intervene and take the case up to the Supreme Court, they are probably going to win. So the dispute over whether Republicans can intervene is frequently a proxy war for who will win the case.

As such, the question of whether Republicans can intervene in litigation controlled by elected Democrats has acquired great practical significance. Not coincidentally, the Supreme Court has developed an intense interest in this heretofore obscure topic, granting certiorari three times last term:

In Cameron v. EMW Women’s Surgical Center, a Democrat (Andy Beshear) replaced a Republican (Matt Bevin) as governor and stopped defending a Kentucky abortion law; the Supreme Court held that the Republican Attorney General (Daniel Cameron) was entitled to intervene to defend the law.

In Berger v. North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, the Republican legislature passed a voter ID law, overriding a veto of the Democratic governor (Roy Cooper). The local NAACP branch sued. The defendants were state officials appointed by Governor Cooper; their lawyer was North Carolina’s AG, Josh Stein, also a Democrat. The Court held that the Republican legislative leaders were entitled to intervene to defend the law.

Arizona v. City and County of San Francisco is extremely complicated, but simplifying mercilessly, the Trump Administration enacted a rule making it much easier to classify immigrants as “public charges” ineligible to obtain green cards. Lawsuits were filed, the Biden Administration stopped defending the rule in court, and Arizona tried to intervene. The case was so procedurally tangled that the Supreme Court ended up dismissing it, but with a concurring opinion by four Justices expressing displeasure with the administration’s maneuvers.

Note the subject matter of these cases: an abortion law, a voter ID law, and a Trump-era immigration restriction. These are exactly the kinds of laws that Democratic officials dislike, Democratic-appointed judges tend to strike down, but the current Supreme Court is likely to uphold—as long as there’s a Republican available to file a cert petition. That is why this topic is so consequential, and why the Supreme Court is so interested in it. The Court’s decision to grant certiorari on this issue again in the Title 42 dispute reflects the same dynamic.

Get to the point, was the Supreme Court’s stay order right or wrong?

I’m not sure I’d say it was right, but it wasn’t wrong either. It definitely didn’t reflect “five conservative justices advancing a conservative political agenda, in violation of clear legal rules,” as Professor Chemerinsky thought. Actually, when one applies the stay factors, filtered through the majority’s philosophical viewpoints, the stay order makes perfect sense.1

In deciding whether to grant a stay, the Supreme Court considers: (1) likelihood of granting certiorari; (2) likelihood of success on the merits, and (3) irreparable harm. In close cases, the Court also considers factors such as the balance of equities and the public interest. Walking through those factors:

(1) The “likelihood of granting certiorari” factor doubtless favored granting a stay given that the Supreme Court granted certiorari in the same order. Was the decision to grant certiorari right or wrong? This can’t really be answered objectively because the decision to grant certiorari is totally discretionary. It turns on whether the Supreme Court thinks an issue is important enough to hear. You can see why the Court would think the issue is important. As explained above, intervention has suddenly become an important topic to the current Court. The subject matter of this case, Covid and border closures, is also important.

(2) The “likelihood of success on the merits” factor also favors granting a stay. Assuming the Court holds that the states have standing and the case isn’t mooted some other way, the D.C. Circuit’s decision is going to be reversed, at least 6-3, possibly 7-2 (with Justice Kagan joining the majority), possibly even 9-0.

The D.C. Circuit said that Arizona filed its motion to intervene too late, and should have moved several months earlier, when the CDC decided to lift the Title 42 order. At that point, held the D.C. Circuit, Arizona should have been able to foresee that the CDC wouldn’t seek a stay.

Now, having had the pleasure of litigating against the government many times, I can attest that it is obvious what would have happened if the Republican AGs had moved to intervene months earlier. The government would have opposed the motion, saying something like: “It is speculative to say to that we will hypothetically not move to stay after hypothetically appealing a hypothetical summary judgment decision that hypothetically enjoins the Title 42 Order, which no one would care about anyway unless a different court hypothetically blocks the repeal of the Title 42 Order and appellate courts hypothetically decline to block that block.” The government would also have said that it is an unnecessary waste of time to have Republican AGs file separate briefs on every motion purely so they could preserve their rights if that hypothetical possibility arises. And, the district court would have, rightly, denied that motion. The Supreme Court will hold that one doesn’t have to intervene to seek a stay until the government decides it won’t seek a stay. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.

The Supreme Court’s stay order also observed that the underlying merits of the case are relevant to the intervention motion. This makes sense: why waste everyone’s time and let someone intervene in a hopeless appeal! The Court will hold that the underlying merits favor intervention. I admire the D.C. court’s well-crafted opinion, but the chances of the Supreme Court invalidating a Covid-era immigration restriction supported by both the Trump and the Biden Administration are extremely slim.

(3) Irreparable harm. The states’ asserted harm is that immigrants will enter their borders and impose costs. If one accepts the premise that this is a “harm,” then that harm is “irreparable” in that an immigrant who lawfully enters and seeks asylum can’t be removed if the Title 42 order is ever reinstated. And if you’re a conservative-leaning Justice, you definitely think there’s irreparable harm, and that the equities and public interest favor leaving the Title 42 order in place.

But wait … does this mean that clear legal rules required the Supreme Court to grant the stay? Was it the dissenters who weren’t following the law?

Also no. What’s doing the work here are legal standards that give the Court essentially infinite discretion.

First, the decision to grant a stay turns on the likelihood of granting certiorari. The decision to grant certiorari is completely discretionary. There are some types of cases in which the Court, by tradition, grants certiorari (e.g., cases with conflicts of authority or cases where a federal statute is invalidated), but this is discretionary and there is no legal rule requiring the Court to grant certiorari in any case.2 And, in lots of cases, such as Arizona v. Mayorkas and many others, there is no conflict of authority. The Court grants certiorari purely because the Court thinks the case is important enough for a grant of certiorari. There are no neutral principles or judicially manageable standards governing what issues are “important enough”; the Justice simply reflects on whether she believes the issue is important. Inevitably, Justices with conservative political commitments will think conservative issues are important, and Justices with progressive political commitments will think progressive issues are important.

Second, the soft factors—irreparable harm, balance of equities, public interest—also have a heavily discretionary component. Historically, courts of equity applied those factors in deciding whether to grant injunctions in fact-specific cases. Should the court grant specific performance of a non-compete? Order a business to remove an infringing product from the marketplace? A judge’s overall philosophy might influence her approach to those issues, but ultimately she would decide based on the specific facts. But the Supreme Court has to apply those equitable factors to broad questions of social policy. Does the “balance of equities” and the “public interest” favor states seeking to slow the flow of asylum applicants, or the applicants themselves? Again, judicially manageable standards do not exist to balance the benefits and harms of general policies. The Justices have little choice but to vote according to their underlying political commitments.

There is much more to say on this topic, but this seems like a good stopping point. In next week’s post, I’ll switch to a different topic, probably something about patents.

(Disclaimer: this post reflects my views, not the views of Jenner & Block.)

I’m going to bracket a crucial question in the case … whether the plaintiff states have standing. I think they don’t, but that’s the subject for another post. The Supreme Court is considering state standing in another case this Term (United States v. Texas), yet another case in which a federal district court in Texas enjoined the Biden administration from pursuing an immigration policy, so we’ll see how that goes.

There are a few types of direct appeals from district courts that the Supreme Court is required to hear (certain types of redistricting cases, constitutional challenges to a few federal statutes, and some other cats and dogs). But that’s only one or two cases per year, sometimes zero.