They didn't submit a photocopy that wasn't required

Why abortion won't be on the Arkansas ballot in November

On August 22, 2024, the Arkansas Supreme Court held, by a 4-3 vote, that an abortion-rights ballot initiative would not appear on the 2024 ballot. Why? It’s a confusing decision, but boiled down, it’s because when the ballot initiative sponsor submitted its petition on the due date, it failed to staple a photocopy of a document it had already submitted a week earlier. The court reached this conclusion even though (a) nothing in Arkansas law requires this photocopy to be stapled; and (b) even if this requirement existed, Arkansas law is clear that the failure to staple this photocopy is curable, and the sponsor immediately cured the asserted defect.

The Arkansas Supreme Court’s decision is wrong. Moreover, the proceedings in this case make clear that Arkansas state officials are unapologetically engaging in viewpoint discrimination, interpreting the law in one way for ballot initiatives sponsored by conservative groups and in the opposite way for ballot initiatives sponsored by progressive groups.

Returning the issue of abortion to the people

In the years since Dobbs, there have been several statewide referenda related to abortion. Each time, the pro-choice side has prevailed, even in conservative states. In Kansas, which voted for Trump by 15% in 2020 and which has not elected a Democratic senator since 1932, a pro-life constitutional amendment failed in 2022 by a remarkable 18%. In Kentucky, which voted for Trump by 26% in 2020, a pro-life constitutional amendment failed in 2022 by 4.7%.

Emboldened by these results, supporters of abortion rights in numerous states have attempted, where state law allows, to put initiatives related to abortion on the ballot. One of those states is Arkansas.

Arkansas bans abortion from the moment of conception, except when necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman. There are no exceptions for rape, incest, fetal anomaly, or cases in which the woman’s health is at risk.

Under Arkansas law, citizens may initiate ballot initiatives for purposes of amending the state constitution. For an initiative to be placed on the ballot, a sponsor must file a petition with the Arkansas Secretary of State with the signatures of ten percent of Arkansas’s legal voters. The petition must also satisfy various other statutory requirements, which I’ll get to.

On July 5, 2024—the deadline for submitting petitions—a citizen group known as Arkansans For Limited Government (AFLG) filed a petition seeking to put a proposed constitutional amendment on the ballot that would have legalized abortion up to 18 weeks, or later in cases of rape, incest, fetal anomaly, or to protect the woman’s health. The number of signatures accompanying the petition far exceeded the 10% threshold. Arkansas is politically similar to Kentucky—both states gave 62% of their vote to Trump in 2020—so this amendment had a strong chance of prevailing.

From the perspective of state officials who supported the abortion ban, the only way to keep abortion illegal in Arkansas was to prevent Arkansans from voting on it. And that’s exactly what happened. The Secretary of State quickly rejected the petition, finding that it did not satisfy statutory requirements. Litigation erupted. After various twists, turns, and shifts in the Secretary’s legal position, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled, by a 4-3 vote, that the initiative wouldn’t appear on the ballot.

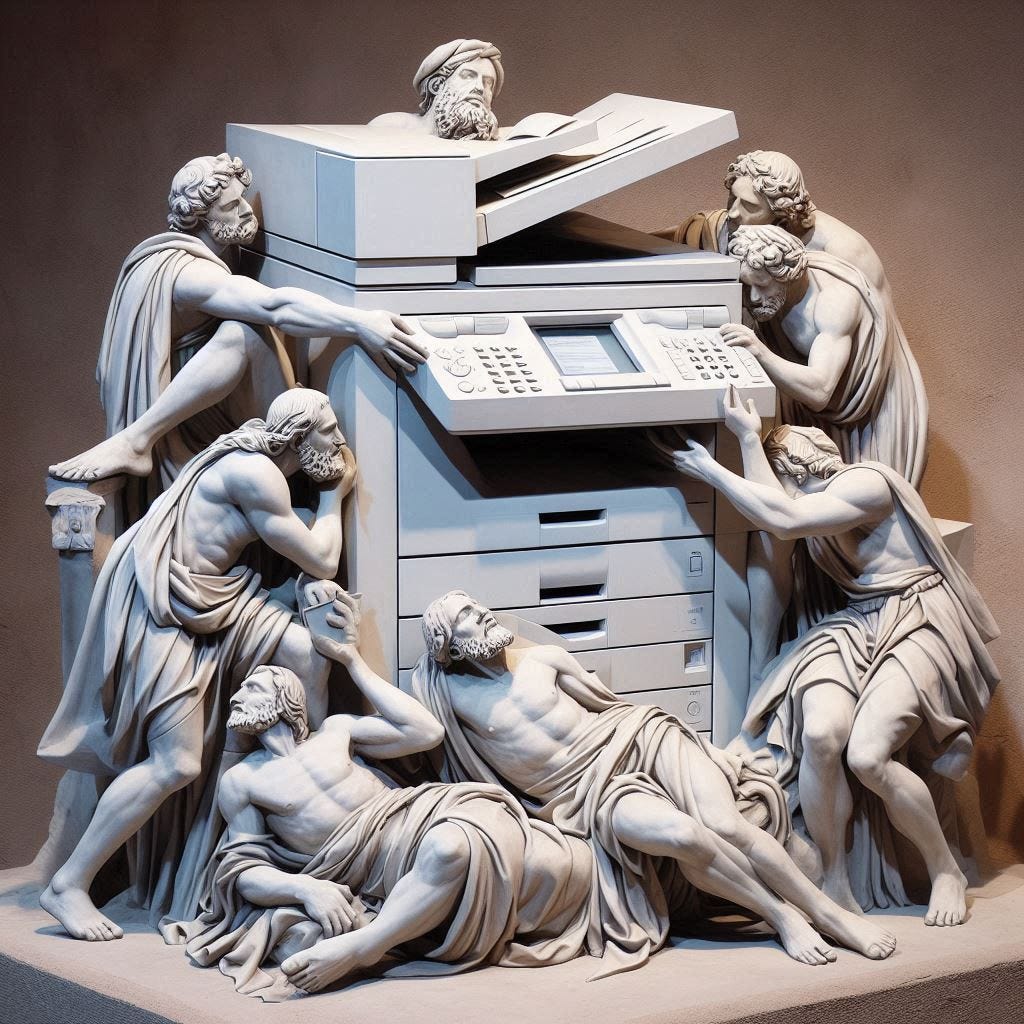

Xeroxgate

Cutting to the chase, the Arkansas Supreme Court held that the petition failed to satisfy Arkansas Code § 7-9-111(f)(2)(B)(ii). Here’s what Section 7-9-111(f) says:

(f)(1) A person filing statewide initiative petitions or statewide referendum petitions with the Secretary of State shall bundle the petitions by county and shall file an affidavit stating the number of petitions and the total number of signatures being filed.

(2) If signatures were obtained by paid canvassers, the person filing the petitions under this subsection shall also submit the following:

(A) A statement identifying the paid canvassers by name; and

(B) A statement signed by the sponsor indicating that the sponsor:

(i) Provided a copy of the most recent edition of the Secretary of State's initiatives and referenda handbook to each paid canvasser before the paid canvasser solicited signatures; and

(ii) Explained the requirements under Arkansas law for obtaining signatures on an initiative or referendum petition to each paid canvasser before the paid canvasser solicited signatures.

Some of AFLG’s signatures were obtained by paid canvassers. The Arkansas Supreme Court rejected the petition because the sponsor purportedly violated Section 7-9-111(f)(2)(B)(ii)—i.e., the requirement that the sponsor submit a statement indicating that the sponsor “explained the requirements under Arkansas law for obtaining signatures on an initiative or referendum petition to each paid canvasser before the paid canvasser solicited signatures.” Let’s call that the Explanation Statement requirement.

To be clear, the sponsor did, in fact, explain the requirements to the paid canvassers, and the court didn’t hold otherwise. Instead, the court held that the sponsor didn’t submit a Explanation Statement that complied with the statute.

So, did the sponsor really flunk the Explanation Statement requirement, and did that failure warrant bouncing the initiative from the ballot?

Here’s what happened.

On June 27, a whole bunch of signatures that were collected by paid canvassers were submitted, accompanied by an Explanation Statement.

Then, on June 29 and July 4, extra signatures that were collected by paid canvassers were submitted, not accompanied by an Explanation Statement.

On July 5 (the deadline under state law), the sponsor submitted the petition, but didn’t attach an Explanation Statement.

The Secretary of State rejected the petition, pointing to the lack of an Explanation Statement.

Relying on a provision of Arkansas law permitting sponsors to cure defective petitions within 30 days, the sponsor submitted an Explanation Statement on July 11. The Secretary of State said: too little, too late.

AFLG sued.

In court, the Secretary of State argued, and the court agreed, that all of the signatures collected by paid canvassers had to be thrown out. Not just the signatures submitted on June 29 and July 4! Even the signatures submitted on June 27, which were accompanied by an Explanation Statement!

Because all of those signatures were tossed, the sponsor came up barely short of the number of signatures needed to qualify for the ballot. The required number was 90,704, and when the signatures gathered by paid canvassers were subtracted, the proponents had 87,765.

Let’s walk through the court’s reasoning. As noted above, the court’s reasoning is confusing and it’s hard to tell how all the pieces of this opinion fit together, but I’ll do my best.

AFLG’s argument went like this:

AFLG submitted an Explanation Statement on June 27, which covered most of the signatures.

Sure, AFLG didn’t submit Explanation Statements accompanying the June 29 and July 4 signatures, but even if you throw those out, you should at least consider the June 27 signatures.

Anyway, as to the June 29 and July 4 signatures, AFLG should have the chance to cure the defect.

Article 5, Section 1 of the Constitution of Arkansas says: “If the Secretary of State … shall decide any petition to be insufficient, he shall without delay notify the sponsors of such petition, and permit at least thirty days from the date of such notification, in the instance of a state-wide petition … for correction or amendment.”

Section 7-9-111 (the same section that contains the Explanation Statement requirement) similarly contains an explicit 30-day cure period.

These provisions fit this case like a hand in glove. The Secretary decided the petition to be insufficient because of the lack of the compliant Explanation Statement. This should have triggered the 30-day cure period. And AFLG cured the defect within a week.

That looks like an open-and-shut argument to me, but it lost.

The court held that the Explanation Statement had to be submitted with the petition on July 5. According to the court, the Explanation Statement submitted on June 27 was meaningless because it wasn’t stapled to the petition. As a result, all of the signatures collected by paid canvassers, including the signatures submitted on June 27 alongside the Explanation Statement, had to be set on fire.

And, even worse, the supposed defect couldn’t be cured! As noted above, the Arkansas Constitution states that if a petition is “insufficient,” there’s a 30-day cure period for “correction or amendment.” Section 7-9-111 includes similar language. But according to the Arkansas Supreme Court, because the June 27 Explanation Statement was submitted too early and therefore doesn’t count, “[t]here was a complete failure to file the paid canvasser training certification along with the petition.” And so there couldn’t be correction or amendment, because “‘[c]orrection and amendment go to form and error, rather than complete failure.’”

If the sponsor had stapled a photocopy of the Explanation Statement that had already been submitted on June 27 to the submission on July 5, the sponsor would have prevailed. There would have been an Explanation Statement with respect to the June 27 signatures. And there wouldn’t have been a “complete failure to file” the Explanation Statement, which would have opened the door to cure the defect—which the sponsor did by July 11. But due to this critical failure to staple a document that had already been submitted, the sponsor lost.

OK, but rules are rules, right? As dumb as this seems, shouldn’t we enforce the law, through hell or high water?

Maybe, if the law actually required this outcome. But it doesn’t. The Arkansas Supreme Court’s key analytical move was its holding that the Explanation Statement must be submitted with the petition. I’m going to paste Section 7-9-111(f)(2) below again, and I am going to ask you to find me the place where it says that the Explanation Statement must be submitted with the petition.

(2) If signatures were obtained by paid canvassers, the person filing the petitions under this subsection shall also submit the following:

(A) A statement identifying the paid canvassers by name; and

(B) A statement signed by the sponsor indicating that the sponsor:

(i) Provided a copy of the most recent edition of the Secretary of State's initiatives and referenda handbook to each paid canvasser before the paid canvasser solicited signatures; and

(ii) Explained the requirements under Arkansas law for obtaining signatures on an initiative or referendum petition to each paid canvasser before the paid canvasser solicited signatures.

It is not there.

Even more amazingly, there’s another section of Arkansas law dealing with paid canvassers that specifically states what information has to be submitted with the petition. It’s Arkansas Code § 7-9-601, which we’ll hear more about later. Here’s what it says (emphasis added):

(3) Upon filing the petition with the Secretary of State, the sponsor shall submit to the Secretary of State a:

(A) Final list of the names and current residential addresses of each paid canvasser; and

(B) Signature card for each paid canvasser.

And the sponsor did, in fact, submit those things upon filing the petition!

There’s no analogous requirement that the Explanation Statement be submitted “upon filing the petition with the Secretary of State.” So AFLG submitted the Explanation Statement early, and didn’t resubmit it because the law says you don’t have to.

I cannot improve on the dissent’s commentary on this issue:

As an initial matter, subsection (f) demonstrates that there is no contemporaneous filing requirement associated with the submission of the certification. It is undisputed that Allison Clark, the controller of Verified Arkansas, LLC, 1 submitted multiple paid canvasser training certifications to the respondent’s office on behalf of the petitioners with each subsequent list being cumulative of the previous list. The last certification was submitted to the respondent on June 27, 2024, and included all paid canvassers that had been hired by that date. The petitioners’ decision to file this certification on a rolling basis clearly satisfied the requirements set forth in subdivision (f)(2)(B) because the certifications were submitted well before the July 5 petition deadline. The fact that the petitioners did not file a certification contemporaneously with the petition is of no moment. To be clear, nothing in the statute requires that the certification and the petition be filed simultaneously. On the contrary, this requirement was made up out of whole cloth by the respondent and inexplicably ratified by the majority of this court.

And then the dissent sums it up:

It is absurd to hold that a certification cannot be submitted early, and by concluding otherwise, the majority has added yet another obstacle that prevents Arkansans from exercising their constitutional rights.

The majority opinion does not respond to this reasoning. It just asserts, without explanation, that “[t]here was a complete failure to file the paid canvasser training certification along with the petition.”

AFLG submitted a sworn declaration alongside its brief stating that in a phone call on approximately July 1, Josh Bridges, the Secretary’s Assistant Director of Elections, told AFLG that submitting an additional Explanation Statement was unnecessary. This seems plausible to me—the government official would sensibly say “you don’t have to resubmit a photocopy of a document you’ve already submitted, given that we already have it and nothing in state law says you have to submit it again,” and for one brief, shining moment, AFLG’s organizers would think they lived in a state where the government operated rationally.

In the litigation, AFLG argued that the Secretary was bound by Mr. Bridges’ representations, but the court rejected this argument on the ground that the law is the law, no matter what the Assistant Director says. I am not questioning the court’s reasoning on this issue, but it makes this episode particularly depressing. Even more depressingly, after the Secretary executed this bait and switch and rejected the petition, Arkansas state officials immediately started mocking AFLG’s organizers for their incompetence. Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders declared: “Today the far left pro-abortion crowd in Arkansas showed they are both immoral and incompetent.” Attorney General Tim Griffin, who litigated the case on the Secretary’s behalf, similarly announced: “Failure to follow such a basic requirement is inexcusable: the #abortion advocates have no one to blame but themselves.” I can think of a few other people to blame.

No doubt

So far I’ve accepted the Arkansas Supreme Court’s premise that if there really was a “complete failure” to satisfy the Explanation Statement requirement, then the signatures can be discarded. That premise is wrong.

What happens when signatures don’t satisfy a statutory requirement? Arkansas law is admirably clear on this issue. Some defects require signatures to be thrown out. Others don’t.

Arkansas divides its requirements related to paid canvassers into three sections: Arkansas Code §§ 7-9-126, 7-9-601, and 7-9-111.

Section 7-9-126 lists a bunch of requirements. If they’re not obeyed, then the “petition part and all signatures appearing on the petition part shall not be counted for any purpose.” One of those requirements includes a cross-reference to Section 7-9-601: “The canvasser is a paid canvasser whose name and the information required under § 7-9-601 were not submitted or updated by the sponsor to the Secretary of State before the petitioner signed the petition.”

Section 7-9-601 lists a bunch of requirements related to paid canvassers, including the requirement to explain Arkansas law to the canvassers. Similar to Section 7-9-126, it says: “Signatures incorrectly obtained or submitted under this section shall not be counted by the Secretary of State for any purpose.”

Section 7-9-111 includes the requirement that AFLG purportedly flunked—i.e., the Explanation Statement requirement. Unlike Sections 7-9-601 and 7-9-126, Section 111 does not include any “do not count” language. Instead, it includes a provision—Section 111(d)—explaining how defects in petitions can be cured.

Just to review here:

Violation of requirement to explain Arkansas law to canvassers: Arkansas law says, “Do not count.”

Violation of requirement to staple statement confirming that Arkansas law was explained to canvassers: Arkansas law doesn’t say “Do not count,” and a nearby provision prescribes an explicit cure mechanism.

It is therefore clear that if you violate the Explanation Statement requirement, the signatures aren’t discarded and you get to cure the violation. How clear? Here are Claude 3.5 Sonnet’s suggestions for “particularly emphatic synonyms for ‘utterly’”: Absolutely, Completely, Entirely, Thoroughly, Wholly, Totally, Unequivocally, Categorically, Downright, and Undeniably. My favorite is Downright. It’s downright clear.

The text is so downright clear that you don’t need to get into policy, but for what it’s worth, this scheme makes perfect sense. If the canvassers collected signatures without understanding the law, then the bell can’t be unrung. The signatures are tainted. So it makes sense that you wouldn’t count them. But if the canvassers were trained and the sponsor simply forgot to staple the document, that’s curable. You can just submit the document you forgot to submit.

One other data point: in a 2016 Arkansas Supreme Court case called Benca, it was undisputed that failures to comply with Section 111(f) were curable. Here’s what the Secretary of State said in his brief: “The express designation of a ‘do not count’ penalty in other subsections of the Arkansas Code … indicates that the absence of such a provision in 7-9-111 was an intentional omission.” The court didn’t question that assumption.

OK, so how does the Arkansas Supreme Court get around this? Section 111(f) specifies that the sponsor “shall” submit the Explanation Statement, and so the Arkansas Supreme Court emphasizes that “shall” means “shall.” But this isn’t a basis to throw out the signatures. “Shall” does indeed mean “shall,” but this observation doesn’t answer the question of whether a violation of the “shall” requirement can be cured.

The Arkansas Supreme Court’s response to this point appears in a footnote. They say that footnotes are where the skeletons are buried, and the Arkansas Supreme Court delivers a museum-quality T-Rex. Take a deep breath:

In Benca, we did not dispute the special master’s finding that § 7-9-111(f)(2) was not attached to a specific “do not count” provision. However, Benca was decided in 2016, before the legislature amended the statute and changed the do not count provision attached to § 7-9-601. In 2019, the General Assembly modified the statute, deleting and amending the ‘do not count’ provision to broaden its applicability. The statute now provides that ‘[s]ignatures incorrectly obtained or submitted under this section shall not be counted by the Secretary of State for any purpose.’ Ark. Code Ann. § 7-9-601(f) (removed from its former location at §7-9-601(b)(5) (Repl. 2018) and modified) (emphasis added).

What’s this business with Section 601(b)(5) and Section 601(f)? Well, before 2019, the “do not count” provision appeared in Section 601(b)(5), which meant that it applied only to the requirements in Section 601(b). In 2019, the “do not count” provision was moved from Section 601(b)(5) to Section 601(f), meaning that it now applies to all the requirements in Section 601, not just the requirements in Section 601(b).

What does this have to do with this case, in which the sponsor is accused of violating Section 111, not Section 601? The answer is nothing.

The Arkansas Supreme Court’s footnote then states:

This leaves us with no doubt as to the intent of the General Assembly to exclude for any purpose the signatures obtained or submitted by paid canvassers that do not meet statutory requirements.

Perhaps the fact that the General Assembly did not, in fact, change the law as to Section 111 should have triggered some doubt.

The Arkansas Supreme Court’s reasoning is kind of like this:

Before 2019, the legislature imposed a $100 mandatory fine on speeding, but not on littering or jaywalking.

In 2019, the legislature changed the law to impose the $100 mandatory fine on both speeding and littering, but didn’t change the law on jaywalking.

“This leaves us with no doubt” that the legislature intended to impose the $100 mandatory fine on jaywalking.

Schrodinger’s signature

The Arkansas Supreme Court offers one other justification for tossing all of the signatures—even the ones that were submitted on June 27, accompanied by the Explanation Statement.

Section 111(f)(2)(B)(ii) specifies that the sponsor must provide “a statement” saying that Arkansas’s requirements were submitted to “each paid canvasser.” The Arkansas Supreme Court offers the following textual analysis:

“A statement” is not multiple statements. The plain meaning of “a” is settled. This court has recently explained “a” as meaning singular rather than plural. … It is one single statement at one specific point in time. Also, the statement must cover “each paid canvasser,” not some of the paid canvassers. It is undisputed, even by the dissenting justices, that there was not a paid canvasser certification filed for “each paid canvasser.”

As I understand it, the Arkansas Supreme Court is advancing the following theory:

Sure, the June 27 Explanation Statement covered “each paid canvasser” up until then.

But, on June 29 and July 4, there were new canvassers added.

Therefore, the June 27 Explanation Statement doesn’t cover “each paid canvasser” anymore.

And so, the June 27 Explanation Statement can be thrown out, thus nullifying all of the signatures collected by paid canvassers, including those submitted on June 27.

Based on this theory, the Arkansas Supreme Court declares:

The dissenting justices want to argue that well, despite this we should give partial credit for the partial attempt to comply. But this is not how a mandatory law works. This court does not ever hold that shall means “just as long as you try”.

Ooh, sick burn. But do you see the problem with this reasoning? If you think the June 29 and July 4 signatures are defective because they’re not accompanied by an Explanation Statement, then toss them! Fine! Then all you have left are the June 27 signatures, accompanied by the Explanation Statement that is, in fact, “a” statement that applies to “each” canvasser.

Once again, the dissent’s analysis of this issue is dead on:

At no point do I give the paid canvassers “partial credit for the partial attempt to comply” with the statute at issue. Rather, my analysis affords “full credit” to the 191 paid canvassers included on the June 27 cumulative list and certification because this was a complete list covering each paid canvasser that had been hired by that date. Stated differently, the June 27 submission was not a “partial attempt” to comply by the petitioners; rather, it was full compliance as to the 191 paid canvassers. Contrary to the majority’s tortured statutory analysis, while there were paid canvassers hired after June 27, nothing in the statute justifies the exclusion of the signatures collected by the paid canvassers included with the June 27 certification.

The Arkansas Supreme Court is treating the June 29 and July 4 signatures as simultaneously alive and dead. Dead, for purposes of finding that they’re defective. Alive, for purposes of putting the canvassers who collected those signatures in the same bucket as the canvassers who collected the June 27 signatures, so that lo and behold, one can say that the June 27 Explanation Statement doesn’t apply to “each canvasser.” It’s like Schrodinger’s signatures.

And what’s the effect of this? A single defective signature—more specifically, a single signature unaccompanied by a statement that the canvasser who collected the signature was trained—taints all signatures. This is because the Explanation Statement ceases to be a single document that applies to “each canvasser,” which means the whole Explanation Statement can be discarded. Why would the law work this way?

AFLG points out that the Secretary has never followed this interpretation in the past. In fact, in the Secretary’s own guidelines to his staff, the Secretary says that if a signature was collected by a canvasser for whom there’s no training certification, you toss the signature and move on to the others. You don’t treat a single defective signature as tainting all signatures. This is the rational way to operate, which is probably why the Secretary never dreamed up this interpretation until he needed to find a way to disqualify the abortion initiative.

***

Taking a step back, I have to dwell on the injustice of it all. Arkansans are being disenfranchised. I understand the importance of preventing fraud and ensuring accurate elections, but requiring a proponent to submit a photocopy of something the proponent submitted a week earlier doesn’t deter fraud. And I understand the importance of upholding the rule of law. Hammurabi, King Solomon, blindfolds, scales, I get it. But there really is nothing in Arkansas law that requires, or even permits, this outcome.

To the left, to the right, in the middle

That wraps up my analysis of the Arkansas Supreme Court’s reasoning. But I’d like to address one other argument advanced by the Secretary that the Arkansas Supreme Court ultimately didn’t resolve. It illustrates some of the most brazen viewpoint discrimination I have ever seen from state officials.

Section 111(f) requires that the Explanation Statement be signed by the “sponsor.” One of the Secretary’s arguments for disqualifying AFLG’s petition was that AFLG’s Explanation Statement wasn’t signed by the “sponsor,” but instead by a person affiliated with the paid canvasser. Also, there’s another provision, Section 601(b)(3), that requires the “sponsor” to “certify to the Secretary … that each paid canvasser in the sponsor’s employ has no disqualifying offenses.” The Secretary argued that AFLG’s petition violated Section 601(b)(3) for the same reason—a person affiliated with the paid canvasser submitted this certification, and according to the Secretary, this wasn’t the “sponsor.”

AFLG retorted that the statutory definition of “sponsor” is broad enough to cover the person who signed these documents—it covers not only a person who “who files an initiative or referendum petition with the official charged with verifying the signatures,” but also a person who “arranges for the circulation of an initiative or referendum petition.” AFLG also argued that “sponsor” includes agents of the sponsor, and the signatory was the sponsor’s agent.

AFLG wasn’t the only group trying to get an amendment on the ballot. A group called Local Voters in Charge was trying to get an anti-casino amendment on the ballot. And a group called Arkansans for Patient Access was trying to get a marijuana amendment on the ballot.

Unlike AFLG, Local Voters in Charge is a conservative group: it released a public statement declaring that “the members of LVC oppose the pro-abortion efforts of [AFLG].” But in one respect it is similar to AFLG: it attempted to satisfy Section 601(b)(3)’s certification requirement by having a person affiliated with the paid canvasser sign the certification.

In a state governed by the rule of law, the Secretary of State would have applied Section 601(b)(3) in the same way to both petitions. Although the substance of the proposed amendments differed—one was a progressive cause, one was a conservative cause—the legal issue was identical: does a certification signed by a person affiliated with the canvasser satisfy Section 601(b)(3)? If the answer is “no” with respect to the abortion amendment, then the answer is “no” with respect to the casino amendment.

This isn’t what the Secretary did, though. Instead, the Secretary decided to certify the casino amendment for the ballot, while simultaneously arguing that the Section 601(b)(3) violation rendered the abortion amendment ineligible for the ballot.

An opponent of the casino amendment filed a lawsuit against the Secretary, making the exact same allegation that the Secretary was making in the abortion case—that a signature by the canvasser didn’t satisfy Section 601(b)(3). The Secretary submitted a responsive filing denying that allegation. Thus, in court filings that occurred within days of each other, the Secretary affirmatively argued that the abortion petition should be disqualified under Section 601(b)(3) while simultaneously taking the opposite position with respect to the casino petition.

(The Secretary is not solely to blame here. The Attorney General was representing the Secretary in the litigation and taking these inconsistent positions.)

Meanwhile, as mentioned above, a third group—Arkansans for Patient Access—was seeking to put a marijuana amendment on the ballot. Exactly like the other two groups, Arkansans for Patient Access attempted to comply with Section 601(b)(3) by submitting certifications signed by persons affiliated with the canvassers.

From a political perspective, though, the marijuana amendment was somewhere in between the casino amendment and the abortion amendment—it’s on the progressive side, but less toxic to Republicans than the abortion amendment. And so, not coincidentally, the Secretary decided that Section 601(b)(3) meant a third thing that fell somewhere in between what it meant for the casino amendment and what it meant for the abortion amendment. The Secretary’s position was that signatures submitted before the cure period wouldn’t have to be thrown out, but signatures submitted during the cure period would have to comply with the Secretary’s new interpretation.

The supporters of the casino and marijuana amendments intervened in the abortion case and filed an indignant brief explaining that the meaning of the law does not shift depending on who is filing the petition. As noted above, the Arkansas Supreme Court declined to resolve this issue. But the dissent included a discussion of this issue which, in my opinion, is irrefutable:

Even a cursory review of how the present ballot initiative has progressed since its inception demonstrates that both the respondent and the majority have treated it differently for the sole purpose of preventing the people from voting on this issue. The intervenors argue that the respondent’s absurdity is highlighted by his differing and conflicting positions on each proposed amendment. As to the petitioners, the respondent refused to count any signatures gathered by paid canvassers. The intervenors allege that, as to Local Voters in Charge, the respondent certified its petition for the ballot on July 31, 2024, because the respondent determined that the signatures gathered by the paid canvassers that had been certified by its agents were sufficient. The intervenors allege further that, as to Arkansans for Patient Access, the respondent has recently concluded that additional signatures gathered by paid canvassers—also certified by its agents—during the cure period will not be counted because the respondent allegedly just “discovered” its noncompliance with Arkansas Code Annotated section 7-9-601(b)(3)— another statute related to paid canvassers that requires the sponsor of an initiative petition to submit a certification to the respondent. However, the respondent assured the group that the thousands of signatures gathered by paid canvassers that he had previously deemed valid will remain so, despite any alleged statutory violation—a courtesy that the respondent chose not to extend to the petitioners in the present case. I would be remiss if I neglected to highlight these allegations, as the differing treatment of these petitions is alarming. As set forth above, the initiative is the first power reserved for the people by the Arkansas Constitution. Why are the respondent and the majority determined to keep this particular vote from the people? The majority has succeeded in its efforts to change the law in order to deprive the voters of the opportunity to vote on this issue, which is not the proper role of this court.

***

Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders reacted to the Arkansas Supreme Court’s decision as follows: “Proud I helped build the first conservative Supreme Court majority in the history of Arkansas and today that court upheld the rule of law, and with it, the right to life.” If “upheld the right to life” is a euphemism for “prevented citizens from voting on abortion,” then the Arkansas Supreme Court’s decision certainly did that. But “upheld the rule of law”? Not so much.

I knew Huckabee was a despicable scumwad, but she seems to be following the GQP playlist by going out of her way to prove she is not only DEEPLY dishonest, but flat out stupid as well. Sad that the people of Arkansas are stuck with such an oxygen thief.

And lawyers wonder why the public’s opinion of them is so low….

A profession whose members twist themselves into a pretzel in order to make an argument that defies logic, reason, common sense, AND the plain language of the law is not a profession worthy of respect.