In March 2022, Florida enacted the Parental Rights in Education Act, referred to by its detractors as the “Don’t Say Gay” law. Many individuals and businesses opposed the law. Among them was the Walt Disney Company, which publicly stated that the law “never should have been signed into law” and expressed hope that it would be repealed.

Governor Ron DeSantis responded that Disney’s statement “crossed the line” and that he would “fight[] back.” He did. The Florida legislature, with Governor DeSantis’s enthusiastic support, dissolved the local government entity that previously regulated Disney World and replaced it with a new entity that would be controlled by allies of Governor DeSantis.

Before this change became effective, the outgoing local government entered into contracts with Disney governing certain aspects of Disney World’s future development. In response, both the incoming local government and the Florida legislature purported to extinguish these contracts. For good measure, the Florida legislature also enacted a new law giving the DeSantis administration new authority over Disney World’s iconic monorail.

Disney has sued the DeSantis administration in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida, alleging violations of, among other things, the First Amendment and the Contracts Clause.

Disney’s arguments are correct. The DeSantis administration has violated Disney’s constitutional rights. For Disney, the Northern District of Florida will soon become the happiest place on Earth.

Destroying free speech in order to save it

As noted above, the Florida legislature enacted the Parental Rights in Education Act in March 2022. At the time, the law provided: “Classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” More recently, the Florida legislature has expanded the ban on “classroom instruction” on “sexual orientation or gender identity” up to grade 8.

The law was controversial, in part because no one was exactly sure what it meant. Concerns were expressed that, for example, books depicting same-sex couples would be banned from the classroom, even though books depicting opposite-sex couples would be permitted. A lawsuit was filed challenging the law under the First Amendment, but the lawsuit was dismissed for lack of standing. An appeal of that decision is currently pending.

Disney opposed the new law—and wasn’t bashful about expressing its opinion. Shortly before the law’s enactment, Disney declared: “We oppose any legislation that infringes on basic human rights, and stand in solidarity and support our LGBTQIA+ Cast, Crew, and Imagineers and fans who make their voices heard today and every day.” After Governor DeSantis signed the bill, Disney opined that the legislation “never should have been signed into law” and that Disney’s “goal as a company is for this law to be repealed by the legislature or struck down in the courts.”

After Disney issued that statement, Governor DeSantis gave a remarkable speech that garnered national attention. Governor DeSantis began by mocking Disney’s wokeness. But when asked whether Florida would retaliate against Disney, he said no. He gave three reasons for taking this principled stance:

First, Governor DeSantis explained, wokeness’s greatest flaw is its chilling effect on free speech. In schools and college campuses, wokeness demands you either be a social justice warrior, or stay silent. Any dissent that might hurt someone’s feelings is characterized as an act of “violence” that warrants punishment. Leadership has to start at the top. Governor DeSantis explained that as a mature, non-woke adult, he wouldn’t be like all those infantile ethnic studies majors who get happy or grumpy depending on whether people agree with them. He defiantly declared: “I don’t care what they’re going to say.” He would ignore Disney’s comments and continue doing what was right for Floridians.

Second: “Go woke, go broke.” As Governor DeSantis elaborated, the government didn’t need to punish Disney. Americans who found wokeness intolerable—a/k/a the vast majority of Americans—would take their business to Sea World. Indeed, wokeness survives only when it is propped up by “civil rights” laws enforced by the government. When the government stays out of people’s way, common sense prevails. His administration would do exactly that: stay out of people’s way.

Finally, Governor DeSantis pointed out, the Parental Rights in Education Act didn’t silence or censor anyone. The notion that the Act somehow chilled free speech reflected the liberal media’s typical lies. Instead, the Parental Rights in Education Act merely prevented government teachers in government schools from propagandizing woke values to small children. The Act reflected the fundamental conservative value that the government should stay out of these debates. In response to Disney’s comments, he’d stick to his principles.

Psych! Of course he didn’t say any of that. Instead, Governor DeSantis decided that the only way to save free speech was to destroy it. He concluded that the solution to wokeness’s implicit chilling of free speech was some good old-fashioned explicit government retaliation for free speech.

Making sewage collection worse

Disney World straddles two counties in Central Florida: Orange County and Osceola County. Long before Disney World opened, Walt Disney recognized that practical challenges would arise if Disney World was simultaneously regulated by two different local governments. Mr. Disney also believed that Disney World would benefit from autonomy in local governance. And the State of Florida said: “be our guest.” In 1967, the Florida legislature established the Reedy Creek Improvement District, a so-called “special district” encompassing about 25,000 acres in Orange and Osceola Counties. Disney World lies within Reedy Creek.

Reedy Creek was governed by a five-member Board of Supervisors. Landowners within Reedy Creek decided who would be elected to the Board of Supervisors. Disney owned the vast majority of the land in Reedy Creek, so as a practical matter, Disney decided who would be elected to the Board. Reedy Creek was in charge of boring but crucial local government services, such as arranging for sewage and waste collection, building roads, providing emergency services, and regulating land use.

Although Disney had considerable autonomy in the provision of humdrum local government services, it was still subject to the jurisdiction of state regulators. It also paid state taxes, and lots of them—in fact last year it paid over $1 billion in Florida state and local taxes.

This arrangement worked out extremely well for both Disney and Florida. Disney World employs more than 75,000 people and is one of the most famous tourist destinations in the world. Indeed, the norm of bringing one’s children to Disney World at one point in their lives has become sufficiently entrenched that it is now widely regarded as an edict of customary international law. Having completed this pilgrimage myself, I can report that sewage and waste collection appeared top-notch and the roads were pothole-free.

After Disney criticized the Parental Rights in Education Act, Governor DeSantis and his allies in the state legislature decided to exact revenge by abolishing Reedy Creek.

Neither Governor DeSantis nor the state legislators attempted to hide the fact that the purpose of this bill was to retaliate against Disney for exercising its First Amendment rights. To the contrary, they openly, proudly touted that this was the purpose of the legislation. The timeline is incredible:

On March 29, 2022, the day after Disney criticized the new legislation, Governor DeSantis declared that Disney’s statement had “crossed the line” and said he would “fight[] back.”

On March 30, 2022, state Representative Spencer Roach announced: “If Disney wants to embrace woke ideology, it seems fitting that they should be regulated by Orange County.”

On March 31, 2022, Governor DeSantis reiterated: “We’re certainly not going to bend a knee to woke executives in California. That is not the way the state’s going to be run.”

According to Governor DeSantis’s memoir, he then worked with the House Speaker to “tackle the potentially thorny issue involving the state’s most powerful company.” He wanted to keep his plans for Reedy Creek secret: “We need the element of surprise—nobody can see this coming.”

On April 19, 2022, Governor DeSantis asked the Legislature to expand a special session so that it could abolish Reedy Creek. That morning, the House representative that sponsored the House’s version of the bill, Randy Fine, announced: “Disney is a guest in Florida. Today we remind them.” He also stated: “You kick the hornet’s nest, things come up. And I will say this: You got me on one thing, this bill does target one company. It targets The Walt Disney Company.”

On April 20, 2022, Governor DeSantis sent a fundraising email declaring: “Disney and other woke corporations won’t get away with peddling their unchecked pressure campaigns any longer.”

On April 20, 2022, both the House and the Senate passed a bill abolishing Reedy Creek. After the vote, a senator declared: “Disney is learning lessons and paying the political price of jumping out there on an issue.”

On April 22, 2022, Governor DeSantis signed the bill abolishing Reedy Creek. At the signing ceremony, Governor DeSantis gave the following explanation for the bill: “We signed the [Parental Rights in Education Act]. And then, incredibly, they say, ‘We are going to repeal Parents’ Rights in Florida.’ And I’m just thinking to myself, ‘You’re a corporation based in Burbank, California and you’re going to marshal your economic might to attack the parents of my state?’ We view that as a provocation and we are going to fight back against that.”

After the law was enacted, everyone was confused. Reedy Creek was abolished, but what would replace it? After several months of uncertainty, the Florida legislature enacted a bill providing that Reedy Creek’s board members would be selected by the governor. Reedy Creek would also be renamed the “Central Florida Tourism Oversight District.” Once selected, board members could serve for up to 12 years, ensuring that Governor DeSantis’s picks would outlive his administration. An extremely subtle provision of the new bill excluded anyone from board service who, in the preceding three years, had worked for any organization that owns a “theme park or entertainment complex” with at least one million visitors.

Governor DeSantis signed the bill on February 27, 2023. The next day, he published his memoir, entitled “The Courage to Be Free.” In this memoir he explicitly and unapologetically states that this legislation was enacted in order to retaliate against Disney’s exercise of its First Amendment rights. Sample excerpt: “When corporations try to use their economic power to advance a woke agenda, they become political and not merely economic actors. … Leaders must stand up and fight back when big corporations make the mistake, as Disney did, of using their economic might to advance a political agenda.”

Overlooking the principle that “if you can’t say something nice, don’t say nothin’ at all,” Governor DeSantis has threatened to continue retaliating against Disney if Disney dares to exercise its First Amendment rights in the future. Last week, for instance, Governor DeSantis gleefully declared that, now that his appointees exercise authority over Disney World, Disney has been forced to shut up: “Since our skirmish last year, Disney has not been involved in any of those issues. They have not made a peep.” Governor DeSantis has also made clear that if Disney makes a peep, there will be consequences: “People are like: ‘What should we do with this land?’ People have said, maybe create a state park, maybe try to do more amusement parks, someone even said, like, maybe you need another state prison. Who knows? I just think that the possibilities are endless.”

Let me pause for a moment and make a few points that, I think, should be uncontroversial.

First, the only reason that Florida abolished Reedy Creek was to retaliate against Disney for its political speech. No one has ever suggested that Reedy Creek was somehow ineffective in carrying out its duties. Public services are excellent in Disney World. Sewage collection, surface water control, emergency medical services, drainage, bridge maintenance, and all the other quotidian tasks of local government are handled expertly. Realistically, these services are way better in Disney World than anywhere else in Central Florida. There’s a reason Disney World is perhaps the most iconic tourist destination in the world.

Second, it is irrational for control over these responsibilities to turn on Disney’s political speech. As a general matter, I have no clear view on the right way to allocate responsibility for local government services such as sewage management. I am not an expert on Sewage Law, and for that I am grateful. However, Disney’s disagreement with the Parental Rights in Education Act is totally irrelevant to the appropriate allocation of responsibility over these services.

Third, retaliating against Disney for its political speech is not only irrational, but also extremely bad. I can’t believe I actually have to explain this, but it is OK in America to criticize the government. Not only is this a natural right of all persons, including legal persons such as corporations, but it is healthy. Holding the government’s feet to the fire makes the government better. It is not a surprise that countries in which people are not punished for criticizing the government, such as America, are better than countries in which people are punished for criticizing the government, such as North Korea.

There is zero government interest in deterring private businesses from criticizing the government. Engaging in the sort of retaliation that Governor DeSantis openly champions is the sort of thing that causes NGOs and The Economist to give foreign countries ratings of “D” and “F” in Foreign Corruption Indices. It is like extortion or the acceptance of bribes, socially destructive actions with no redeeming qualities. It is the type of government activity that causes foreign dissidents to seek asylum in the United States.

I am amazed that Governor DeSantis’s memoir would be entitled “The Courage to be Free.” Apparently, to Governor DeSantis, “freedom” means the freedom to be free from diversity trainings on college campuses and the like. It does not include the actual freedom that American soldiers have fought and died for in foreign wars, the freedom that gives people goosebumps when they hear the Star-Spangled Banner: the freedom to criticize the government without fear of official retribution.

Does punishing people for their speech violate the First Amendment? Yes, yes it does.

OK, what Florida did is bad. But does it violate the First Amendment?

Disney’s lawsuit against Governor DeSantis alleges that Senate Bill 4C (which abolished Reedy Creek) and House Bill 9B (which replaced it with the DeSantis-controlled Central Florida Tourism Oversight District) are unconstitutional, so this issue is squarely teed up in the Northern District of Florida. In my view, the Northern District of Florida should hold that yes, Senate Bill 4C and House Bill 9B violate the First Amendment. Disney’s statements regarding the Parental Rights in Education Act were constitutionally protected speech. The Constitution does not permit the government to retaliate against Disney for that speech.

Florida’s primary argument to the contrary is that Disney has no constitutional right to the existence of Reedy Creek, so it cannot complain about Florida abolishing it.

However, there is abundant case law holding that the government cannot strip people of benefits because of their political speech, even if there is no constitutional right to those benefits. Under Pickering v. Board of Education of Township High School District 205, 391 U.S. 563 (1968), for instance, public employees cannot be fired for their political speech, even though they have no right to be public employees. Similarly, Board of County Commissioners, Wabaunsee County v. Umbehr, 518 U.S. 668 (1996), holds that terminating at-will government contractors on the basis of their political speech violates the First Amendment. New politicians, when elected to office, cannot turn away and slam the door on the incumbent contractors.

In some ways Disney’s case is easier than Umbehr. Justice Scalia’s dissent in Umbehr—one of his best ever, in my opinion—argues that there is a longstanding tradition of political patronage, and that terminating at-will government contracts of non-patrons is merely the flip side of that patronage. Even if that is true, Disney’s case has nothing to do political patronage. Florida is not rewarding any political speech; it is merely punishing it.

But, Florida’s argument will go, Disney differs from a mere government employee or contractor. The law creating Reedy Creek allows Disney to exercise de facto government power, and the government need not hand power to those that disagree with it.

Well, sure, in some cases the First Amendment shouldn’t protect people who exercise government power. For instance, if the Secretary of State starts bashing the President’s job performance, the Secretary of State doesn’t have a First Amendment right to keep his job. More generally, when a political official is charged with advancing the political agenda of an administration, it makes sense that the political official’s speech be aligned with the administration’s views.

Here, though, neither Reedy Creek nor Disney is a political official charged with advancing the DeSantis Administration’s political agenda. Reedy Creek has existed during the administrations of governors with a wide variety of political views, and it has kept doing the same thing during all of those administrations: expertly handled the day-to-day affairs of local government. In prior administrations, a cold relationship between Disney and its regulators never bothered Disney or the regulators anyway; it shouldn’t be different now.

Moreover, I think this argument overlooks what is really happening here. Florida has not just abolished Reedy Creek. It has also installed a new set of appointees for the purpose of harassing Disney. Again, no one has claimed that these appointees are better at managing garbage collection or emergency services than their predecessors. They are there to carry out Governor DeSantis’s threat that if Disney criticizes the government again, watch out.

In First Amendment cases, the constitutionality of state action frequently turns on whether that state action has a chilling effect on constitutionally protected speech. I’m not trying to be Chicken Little: In my view, Governor DeSantis’s actions have a greater chilling effect on constitutionally protected speech than any state action in modern American history. Governor DeSantis has publicly expressed pride in this chilling effect, making statements such as: “Since our skirmish last year, Disney has not been involved in any of those issues. They have not made a peep.” Other businesses in Florida have undoubtedly recognized that if they criticize the government, they will be punished.

(Maybe Florida will contest Disney’s argument regarding legislative motives, but it should be easy for the court to make the requisite finding. Nemo enetur seipsum prodere—the maxim embodying the right against self-incrimination—is irrelevant here, when the state officials have voluntarily and openly made their motives clear. And of course, doc review during discovery might turn up even more evidence.)

I will acknowledge that there is no Supreme Court case that is directly on point. This case is unprecedented, in part because there is no precedent in modern American history for any governor or legislature acting in the way Governor DeSantis has. Moreover, there are some purists who believe that it is never appropriate to invalidate a law based on the motives of those who enacted it, and never appropriate to attempt to discern the motive of a multi-member legislative body. (My own view is that it is rarely appropriate to do these things, but occasionally motives are so obvious that they cannot be ignored, as in this case.)

Still, though, looking at the overall arc of Supreme Court case law, the Court has been incredibly protective of core political speech. Laws that resulted in subtle, indirect chilling effects were unconstitutional. Here are a few recent examples:

FEC v. Cruz, 142 S. Ct. 1638 (2022): The Supreme Court struck down a law providing that, if a candidate loans money to his campaign, no more than $250,000 of that loan can be repaid via post-election contributions. Here is the theory: “By restricting the sources of funds that campaigns may use to repay candidate loans, Section 304 increases the risk that such loans will not be repaid. That in turn inhibits candidates from loaning money to their campaigns in the first place, burdening core speech.”

Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, 141 S. Ct. 2373 (2021): The Supreme Court struck down a law requiring charitable organizations to disclose to the state Attorney General's Office the identities of their major donors. The theory was that state’s assurances of confidentiality weren’t trustworthy, so there was a risk donors’ identities might leak, which might chill them from associating with the organizations in the first place, which might burden the organizations’ speech.

Janus v. AFSCME, 138 S. Ct. 2448 (2018): Overruling prior case law to the contrary, the Supreme Court held that public employees could not be required to pay money to unions as a condition of public employment, even if the employees were assured that the payment wouldn’t go toward the union’s political activities. The theory was that any compelled payment to a union would violate the employee’s First Amendment rights if it even indirectly assisted the union in advancing a position with which the employee disagreed.

Sure, Disney’s case is distinguishable from all these cases. I’m making a more general point … if we’re willing to enforce the First Amendment in all those cases, and not here when the chilling effect on speech is so much more blatant, what are we doing? I conclude that the abolition of Reedy Creek violated the First Amendment.

Contracts, shmontracts

If Florida had merely abolished Reedy Creek and left it at that, Disney might have been willing to let it go. Things didn’t quite work out that way.

After the legislature decided to abolish Reedy Creek but before the new leadership actually took over, Disney decided that it would not let the storm rage on. Instead, it would protect itself. This part of the story has been the subject of much confusion and inaccurate reporting.

Under a Florida law called the Community Planning Act, special districts (including Reedy Creek) are required to adopt “comprehensive plans” governing future development, and review those comprehensive plans every seven years. Those comprehensive plans are then subject to review by state regulators. In 2022, Reedy Creek approved a Comprehensive Plan setting forth land development plans through 2032. Reedy Creek then sent this plan to Florida’s Department of Economic Opportunity, a branch of state government whose leader is selected by Ron DeSantis. The Department approved the plan. At nearly 400 pages, it is, indeed, extremely comprehensive.

A different Florida law called the Florida Local Government Development Agreement Act authorizes local governments to enter into contracts with private developers governing land use. Essentially, these contracts ensure that land-use rules remain frozen—and there are good reasons those land-use rules should remain frozen. Two such reasons are: (1) encouraging investment and (2) encouraging long-term planning.

In February 2023, Disney entered into a Development Agreement with Reedy Creek, as specifically contemplated by Florida law. The Development Agreement essentially grants Disney assurances that it could continue developing its property according to the terms of its Comprehensive Plan. Reedy Creek also agreed to a Restrictive Covenant, which prevented Reedy Creek from using its land (i.e., land abutting Disney World) for purposes such as head shops and strip clubs.

To protect the public and avoid back-room deals, Florida law requires that before a land development agreement is signed, the agreement be subject to discussion at two public hearings, both of which must be publicly announced in the newspaper. Reedy Creek complied with this requirement. Notice #1 was in the Orlando Sentinel on January 18, 2023. Public Hearing #1, attended by numerous media representatives, was on January 25, 2023. Notice #2 was in the Orlando Sentinel on January 27, 2023. Public Hearing #2 was on February 8, 2023.

Apparently, the DeSantis Administration did not realize this was happening. Perhaps one shouldn’t blame them too much for canceling their Orlando Sentinel subscriptions. The daily front-page stories that, yet again, the Festival of Fantasy Parade has reached Cinderella Castle do get a little dry.

But anyway, neither Governor DeSantis nor anyone else objected at the public hearings. So, on February 8, 2023, the contracts were approved. They were then recorded in county records.

On February 27, 2023, Governor DeSantis signed the bill replacing Reedy Creek’s leadership with gubernatorial appointees. Ushering in a new era of improved surface water management and fire code enforcement, he declared that the new board would prevent Disney from “trying to inject woke ideology” into children.

His new appointees did not disappoint. In March 2023, the new Board found out about the Development Agreement and Restrictive Covenant. One of the new Board members reacted by declaring that Disney had been “allowing radicals to sexualize our children” and had “sneak[ed] in a last minute sweetheart development agreement.”

Governor DeSantis himself did not take the news well. He wrote a letter crediting the new board members for having “uncovered” the agreements, even though the agreements had been officially recorded in county records for two months, after being signed pursuant to a state law explicitly authorizing such contracts, following two public hearings that were advertised in the newspaper and attended by numerous media representatives. He ordered a civil and criminal (!) investigation of these contracts. He also made explicit statements threatening to improperly exercise regulatory authority as vengeance for the contracts, such as: “Now that Disney has reopened this issue, we’re not just going to void the development agreement they tried to do, we’re going to look at things like taxes on the hotels, we’re going to look at things like tolls on the roads.”

It bears noting that neither Governor DeSantis nor the new Board members have identified anything bad about the Development Agreement or the Restrictive Covenant. Again, the Development Agreement codifies a Development Plan that had already been approved by the State of Florida. They simply have malice towards Disney, and therefore oppose any contract that might hinder their ability to threaten Disney.

On April 26, 2023, the new Board declared the Development Agreement and Restrictive Covenant “void and unenforceable.” The new Board also filed a lawsuit in Florida state court attempting to get a declaratory judgment that the agreements are void.

I’ll discuss this lawsuit in a bit; it’s pretty bad. Recognizing the risk that the Board would lose in court, the Florida state legislature decided to pass a statute repealing the Development Agreement and Restrictive Covenant.

The woke Contracts Clause strikes again

No, seriously. This really happened.

On May 5, 2023, Governor DeSantis signed a new bill that purportedly repealed the contracts. Here’s what it says:

An independent special district is precluded from complying with the terms of any development agreement, or any other agreement for which the development agreement serves in whole or part as consideration, which is executed within 3 months preceding the effective date of a law modifying the manner of selecting members of the governing body of the independent special district from election to appointment or from appointment to election.

And, just to show who’s boss, the legislature threw in a new law providing official state oversight over Disney’s monorail. It requires the DeSantis-controlled Department of Transportation to “adopt by rule minimum safety standards” for:

Any governmentally or privately owned fixed-guideway transportation systems operating in this state which are located within an independent special district created by local act which have boundaries within two contiguous counties.

Quite subtle! Also on May 5, Governor DeSantis declared: “This all started, of course, with our parents’ rights bill.”

I find this legislation puzzling. Do voters—even DeSantis voters—really want this? I understand that other recent Florida laws may authentically reflect the views of Governor DeSantis’s base—giving sneezy unvaccinated Floridians the right to keep their jobs, and so on. But are there really lots of voters saying, “what we really want from our governor is for him to mimic the leaders of failed states such as Venezuela”?

But anyway, after Disney’s contracts were canceled, it couldn’t hold it back anymore, and sued. (It originally filed its lawsuit after the Board purported to void the contract, and an amended complaint after the Legislature passed its statute also purporting to void the contract.)

Disney should win.

I’ve already talked about Disney’s First Amendment argument. Disney’s First Amendment argument on the cancelation of the contracts is even stronger than its First Amendment argument on the abolition of Reedy Creek, because the cancelation of the contracts can’t be conceptualized as a mere withdrawal of government authority.

But I’ve said enough about the First Amendment. Let’s turn to Disney’s Contracts Clause challenge. (Disney has other challenges too—Takings, Due Process—that may also be winners, but I’ll skip over those because this post is too long already.)

Suppose a legislature enacted a new law saying: “Henceforth in this state, criminal defendants will not get jury trials.” That would be pretty weird, right? The Constitution guarantees the right to a jury trial. Why would the legislature enact a law that openly touts, “We are violating the Constitution”?

Well, that’s basically what the Florida legislature did here. The Contracts Clause, in Article I of the Constitution, bars states from enacting any “Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.” The new Florida law says that the new Board is “precluded from complying with the terms of” the Development Agreement. Unconstitutional!

OK, fine, the Supreme Court has announced a dopey balancing test for Contracts Clause challenges, where courts first ask whether the law is a “substantial impairment of a contractual relationship” and then ask whether the law is drawn in an “appropriate” and “reasonable” way to advance “a significant and legitimate public purpose.” It’s a pretty tangled area of law, but here, the test is easy to apply. A law canceling a contract substantially impairs the contract. Retaliating against a company for criticizing the government isn’t a significant and legitimate public purpose.

(To aficionados of the Contracts Clause, Governor DeSantis is a big hero. Six years after the Supreme Court last granted certiorari in a Contracts Clause case, it’s nice to see that sleepy constitutional provision back in the news.)

As I understand it, Florida’s defense is based on Fla. Stat. § 163.3241, which states: “If state or federal laws are enacted after the execution of a development agreement which are applicable to and preclude the parties’ compliance with the terms of a development agreement, such agreement shall be modified or revoked as is necessary to comply with the relevant state or federal laws.”

Well, sure, an otherwise constitutional state law might require a contract to be modified or revoked. If the Legislature enacts some health-and-safety law that has the indirect effect of preventing adherence to the terms of a contract, and that law is upheld in court, then the contract might have to be modified or revoked. But § 163.3241 doesn’t authorize the Legislature to explicitly overturn contracts. If it did, it would be unconstitutional. The Legislature can’t enact a law that just preemptively declares: “Who cares about the Constitution, it is perfectly OK for us to enact future statutes repealing pre-existing contracts.”

Florida also argues that the contracts should be canceled because the Reedy Creek officials who signed it were somehow corrupt. Well, there is zero evidence of this in my opinion. But, even if such evidence existed … you might say there’s some longstanding case law on this issue.

The past can hurt. But the way I see it, you can either run from it, or learn from it.

You all know that the first Supreme Court case to strike down a federal statute was Marbury v. Madison. What’s the first Supreme Court case to strike down a state statute?

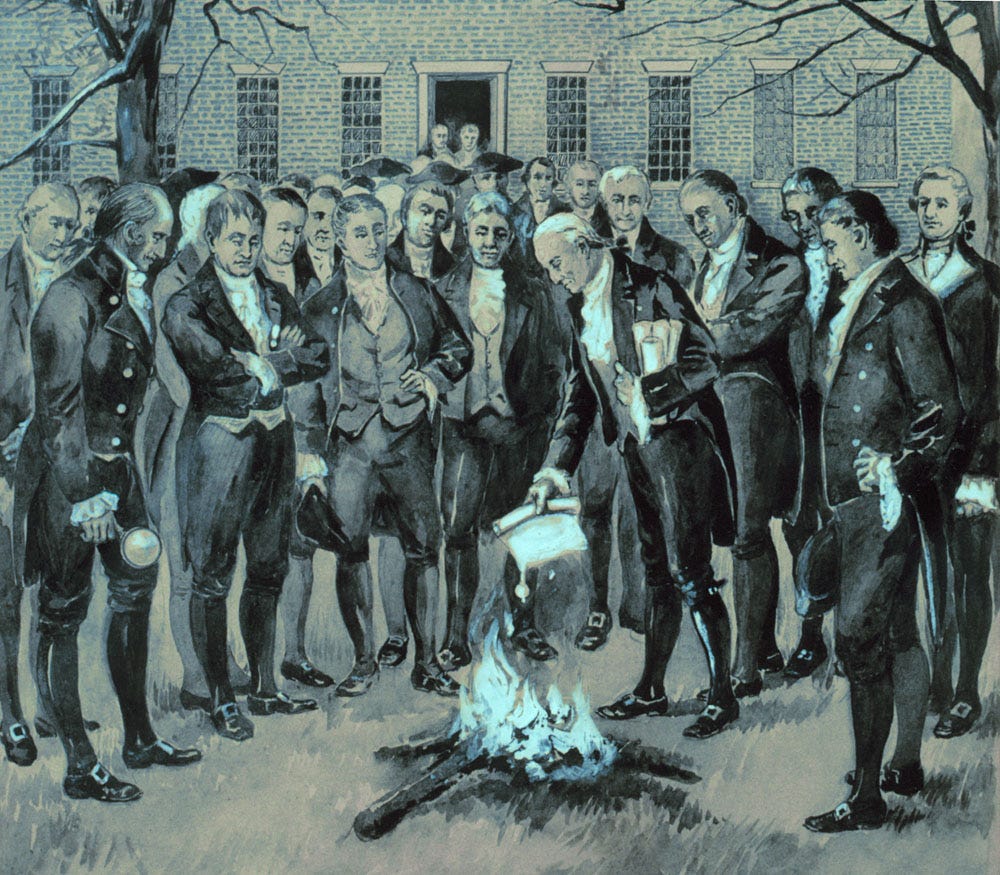

It’s Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. (6 Cranch) 87 (1810).1 Fletcher v. Peck is a case with many layers, but in a nutshell, in 1795, the Georgia Legislature sold land known as the Yazoo Lands to certain companies at a bargain-basement price. It was later revealed that the legislators did this because they took bribes. Not surprisingly, they were not re-elected. In 1796, the next legislature tried to pass a law overturning the land grants. Here’s some artwork of the new legislators:

This isn’t Dall-E; it’s actual artwork of the state legislators setting the land grants on fire.

Beneficiaries of the land grants filed lawsuits, and the case reached the Supreme Court. The Court, per Chief Justice Marshall, ruled that it does indeed have the power to strike down state laws, and Georgia’s law was unconstitutional. It held that the land grants qualified as contracts, and the corruption of the prior legislature wasn’t a defense to the Contracts Clause claim.

213 years later, Fletcher is relevant again. Just as Georgia’s legislators could not set land grants on fire in 1796, Florida’s legislature cannot set Disney’s contracts on fire in 2023. It’s the circle of life.

Ah, but Governor DeSantis merely wanted to give some more control to his appointees! Surely that couldn’t violate the Contracts Clause?

It could. Nine years after Fletcher, Chief Justice Marshall authored the opinion for the Court in an all-time classic, Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 250 (1819). Again, lots going on in this case, but in brief, the New Hampshire legislature enacted a law purporting to repeal Dartmouth College’s charter and to transfer the authority to appoint trustees to New Hampshire’s governor. Following an oral argument by Daniel Webster that is known in legal lore as the greatest of all time (“It is a small college, and yet there are those who love it”), the Supreme Court struck down New Hampshire’s statute under the Contracts Clause.

I understand that Florida is seeking to rewrite its textbooks to place more emphasis on the greatness of the Founding Fathers. In my view, it would be quite educational for textbooks to explain how these famous cases from over 200 years ago require the invalidation of Florida’s unconstitutional law in 2023. I wish upon a star that someone out there is listening.

About that state-court lawsuit…

One more thing.

As I mentioned above, the new Central Florida Tourism Oversight District sued Disney in state court, alleging that the Development Agreement and Restrictive Covenant are void. I understand that state court is a whole new world, but still, the lawsuit is pretty lame, in my opinion.

Among other things, it complains about Disney’s decision to make EPCOT a theme park rather than a residential community, as was originally planned in the 1960s. Seriously?

The lawsuit offers nine theories for why the contracts are void. It’s typical in lawsuits to put your strongest foot forward, so … let’s take a look at Count I, which the new Board presumably thinks is its strongest argument. Count I alleges that the contracts were void because even though Reedy Creek put public notices in the newspaper, it did not also mail the public notices to “all affected property owners,” as allegedly required by state law. The complaint does not identify the “affected property owners” who allegedly failed to receive this mailing. Nor does it suggest these “affected property owners,” if they exist, care about this. Also, the complaint does not explain why a local government should be permitted to void a contract because of the local government’s own alleged failure to notify people who don’t object to the contract.

Another theory in the complaint is that the Development Agreement and Restrictive Covenant are void as against public policy. The complaint relies on Florida’s law giving control of the local government to gubernatorial appointees, which, you’ll recall, was enacted after those agreements were signed. No problem, says the complaint: “Although [the law] was still under legislative consideration on February 8, 2023, when the Development Agreement and Restrictive Covenants were approved and adopted by the RCID, the public policies that the law advances—public oversight and accountability—preexist this particular law.” What a great way to get around contracts! Just pass a new law, declare that the law merely recognizes a public policy that has existed all along, and presto—the contract can retroactively be deemed void as against public policy! I am not sure this argument will fly.

I’m not going to slog through every one of the nine theories, but none, to my eye, has any discernible merit. Disney’s contracts are valid, binding, and should be upheld. And to anyone who reached the bottom of this post, you’ve got a friend in me.

I realize there’s an argument for United States v. Peters, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 115 (1809).

I made it to the end and found the whole thing illuminating and, dare I say, enjoyable.

Thank you for the detailed explanation. Much appreciated.