Mifepristone and the rule of law, part IV

The Fifth Circuit's merits analysis was as wrong as its standing analysis.

In my prior post, I expressed disagreement with the Fifth Circuit’s decision partially denying the FDA’s motion to stay the district court’s order. The bulk of my prior post addressed the Fifth Circuit’s analysis of standing, with only a brief discussion of the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning on the merits.

On the merits, the Fifth Circuit concluded that the FDA acted arbitrarily and capriciously in 2016 when it made certain changes to mifepristone’s safety requirements, and arbitrarily and capriciously again in 2021 when it concluded that an in-person dispensing requirement was unnecessary to protect women’s safety.

These rulings are just as wrong, in my view, as the Fifth Circuit’s ruling on standing. The issues are more technical, so, I am sorry in advance but this post is going to be pretty dry. But still, I don’t want anyone to think that the FDA acted illegally and should win merely because of the technicality of standing. The FDA’s decisions were perfectly reasonable and deserve to be upheld.

Like the district court, the Fifth Circuit concluded that the FDA did not give adequate consideration to women’s safety. To the contrary, however, the FDA gave extensive consideration to women’s safety. The Fifth Circuit offered no analysis of the FDA’s actual reasoning. It simply declared that the FDA did not adequately consider safety. Let’s take a closer look at the FDA’s reasoning and assess whether the FDA shirked its duty to consider safety, as the Fifth Circuit claimed.

Changes to the label in 2016 - FDA’s decision

Mifepristone was initially approved in 2000. In 2016, the FDA relaxed certain safety restrictions. The FDA increased the gestational age limit from 49 to 70 days, reduced the number of required in-person clinic visits to one, and allowed healthcare providers other than doctors to prescribe it.

In support of its decision, the FDA analyzed an extensive body of evidence addressing each of these changes.

First, the FDA analyzed studies involving over 30,000 women regarding the effect of mifepristone (alongside the second drug in the regimen, misoprostol) at up to 70 days gestation. Here’s what the FDA said:

Four studies and one systematic review evaluated the exact proposed dosing regimen through 70 days gestation. These include three prospective observational studies (Winikoff et al 2012, Boersma et al, Sanhueza Smith et al) and one randomized controlled study (RCT) (Olavarrieta et al) that had a primary objective of evaluating medical abortion provision by non-physicians. The systematic review by Chen and Creinin covered 20 studies including over 30,000 women; all but one of the studies used the proposed regimen in gestations through 70 days … For those publications that provided overall success rates, these were in the range of 97-98%. Other relevant publications include the systematic review by Raymond of 87 studies, which covered a variety of misoprostol doses and routes of administration used with 200 mg of mifepristone. Assessing the efficacy by misoprostol dose, the paper noted that doses >= 800 mcg had a success rate of 96.8%, with an ongoing pregnancy rate of 0.7%.

As far as I know, no one has ever disputed that mifepristone and misoprostol work as well at 70 days as they do at 49 days. Based on those studies, the FDA concluded that the gestational age limit could be increased to 70 days.

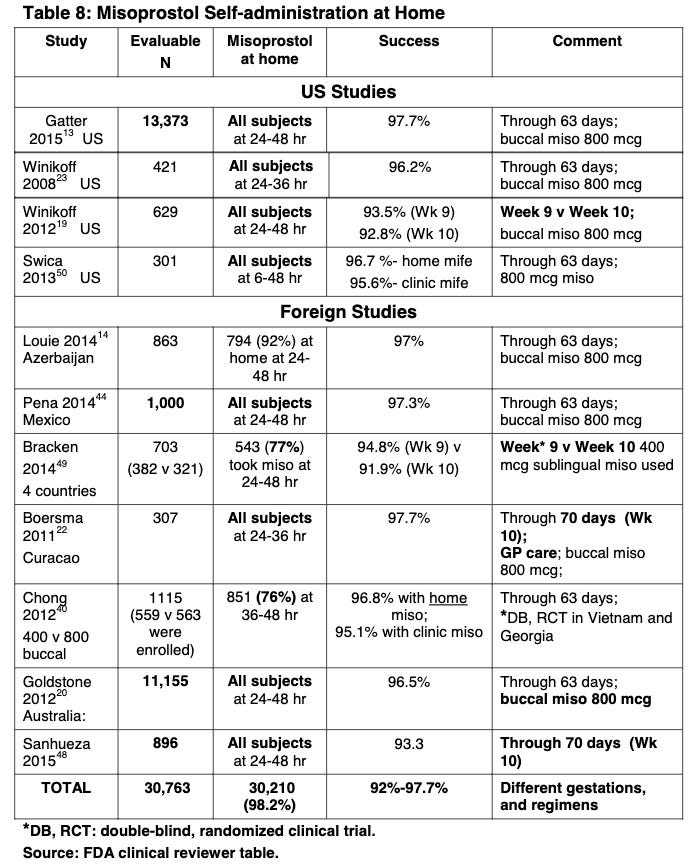

Second, the FDA reduced the number of required in-person clinic visits to one based on 11 studies, with over 30,000 participants, confirming that the home use of misoprostol (i.e., the second drug in the regimen) was safe. Here are the studies:

That’s a lot of studies! Based on this, the FDA concluded:

The studies reported on large numbers of women in the U.S. who took misoprostol at home. The authors showed that home administration of misoprostol, as part of the proposed regimen, is associated with exceedingly low rates of serious adverse events, and with rates of common adverse events comparable to those in the studies of clinic administration of misoprostol that supported the initial approval in 2000. Given that information is available on approximately 45,000 women from the published literature, half of which incorporated home use of misoprostol, there is no clinical reason to restrict the location in which misoprostol may be taken.

Third, the FDA authorized non-doctors to prescribe mifepristone based on “data on the efficacy of medical abortion provided by non-physician healthcare providers, including four studies with 3,200 women in randomized controlled clinical trials and 596 women in prospective cohorts.” According to the FDA’s reviewer, the “studies were conducted in varying settings (international, urban, rural, low-resource) and found no differences in efficacy, serious adverse events, ongoing pregnancy or incomplete abortion between the groups.” One of those studies, for example, was a “randomized controlled equivalence trial of 1,068 women in Sweden who were randomized to receive medical abortion care from two nurse midwives experienced in medical terminations and trained in early pregnancy ultrasound versus a group of 34 physicians with varying training and experience.” The study showed “fewer complications for the nurse midwife group, though this was not statistically significant.”

The FDA also observed:

Midlevel providers are already practicing abortion care under the supervision of physicians, and the approved labeling and the REMS Prescriber’s Agreement already stipulate that prescribers must be able to refer patients for additional care, including surgical management if needed. Therefore, facilities that employ midlevel prescribers already have an infrastructure in place for consultation and referral.

The FDA recognized that it was making several changes at the same time, and therefore should consider studies considering how these changes work together:

As these major changes are interrelated, in some cases data from a given study were relied on to provide evidence to support multiple changes.

For example, the FDA chose at least three studies (Winikoff, Boersma, and Sanhueza) both for purposes of assessing the 70-day gestational age limit and for purposes of assessing home use of misoprostol. In addition, in its assessment of the 70-day gestational age limit, the FDA went out of its way to rely on a study (Olavarrieta) that “had a primary objective of evaluating medical abortion provision by non-physicians.”

Changes to the label in 2016 - Fifth Circuit’s decision

Despite all this, the Fifth Circuit finds that the FDA’s decision was arbitrary and capricious because it did not adequately consider safety.

First, the Fifth Circuit says this:

First, FDA failed to “examine the relevant data” when it made the 2016 Major REMS changes. State Farm, 463 U.S. at 43. That’s because FDA eliminated REMS safeguards based on studies that included those very safeguards. FDA Add. 59, 122–23, 171. Imagine that an agency compiles studies about how cars perform when they have passive restraint systems, like automatic seatbelts. See State Farm, 463 U.S. at 34–36. For nearly a decade, the agency collects those studies and continues studying how cars perform with passive safety measures. Then one day the agency changes its mind and eliminates passive safety measures based only on existing data of how cars perform with passive safety measures. Cf. id. at 47–49. That was obviously arbitrary and capricious in State Farm. And so too here. The fact that mifepristone might be safe when used with the 2000 Approval’s REMS (a question studied by FDA) says nothing about whether FDA can eliminate those REMS (a question not studied by FDA).

I am astonished by this paragraph. How could the Fifth Circuit say that the FDA “eliminated REMS safeguards based on studies that included those very safeguards”? How could it say that “whether FDA can eliminate those REMS” was “a question not studied by FDA”? As explained above, the FDA exhaustively analyzed a massive body of evidence on whether it could eliminate the safeguards. The Fifth Circuit is hoping that people will read this discussion and nod along saying, wow, it was so dumb for the FDA to have made these changes without studying them! It is assuming people will not read the agency record, which shows that the FDA did study them.

Also worthy of note, the Fifth Circuit does not cite or discuss the FDA’s decision at all. Everything I’ve discussed above—all of these exhaustive studies and analyses—is absent from the Fifth Circuit’s decision. Instead, the Fifth Circuit effectively declares that the agency record, which exists, does not exist.

Next, the Fifth Circuit walks back its prior discussion a little bit, and says this:

True, FDA studied the safety consequences of eliminating one or two of the 2000 Approval’s REMS in isolation. But it relied on zero studies that evaluated the safety-and-effectiveness consequences of the 2016 Major REMS Changes as a whole. This deficiency shows that FDA failed to consider “an important aspect of the problem” when it made the 2016 Major REMS Changes. Michigan v. EPA, 576 U.S. at 752 (quotation omitted).

This paragraph is also false. First, the FDA did not merely study the safety consequences of “eliminating one or two of the 2000 Approval’s REMS.” Where exactly is the Fifth Circuit getting “one or two” from? The FDA analyzed all of the changes in exhaustive detail.

Second, the FDA did not study all those changes in “isolation.” Instead, the FDA’s decision observed: “As these major changes are interrelated, in some cases data from a given study were relied on to provide evidence to support multiple changes.” The FDA went out of its way to consider studies that make multiple changes simultaneously; e.g., studies that involve use of mifepristone at 70 days gestation and also involve non-physicians or also involve only a single visit to the clinic. I am at a loss as to what “important aspect of the problem” the FDA failed to consider.

None of the studies were 100% identical in all respects to the new requirements on the label (the FDA’s stay application says that two of the studies were nearly identical to the new requirements on the label, but not 100% identical). The plaintiffs’ argument in the district court, which the Fifth Circuit is buying here (I think?), is that an FDA decision is arbitrary and capricious unless there is a study that is identical to the new requirements on the label. Only such a study, the plaintiffs claim, would ensure that women’s safety is protected.

This purported requirement has no basis in any statute and makes no sense. Under the applicable statute, 21 U.S.C. § 355(d), the FDA may refuse an application if:

Evaluated on the basis of the information submitted to him as part of the application and any other information before him with respect to such drug, there is a lack of substantial evidence that the drug will have the effect it purports or is represented to have under the conditions of use prescribed, recommended, or suggested in the proposed labeling thereof.

“Information submitted to him as part of the application and any other information.” This doesn’t sound like a statutory requirement that the studies be identical in all respects to the label.

Nor does the agency act arbitrarily and capriciously by approving a drug in the absence of a study that is identical in all respects to the label. An agency is allowed to make reasonable inferences from available data. In this case, the FDA relied on multiple studies showing that it was perfectly safe for women to be prescribed mifepristone from non-physicians. An additional 11 studies with 30,000 participants showed that a woman could take misoprostol at home without safety complications. The FDA inferred that if the woman was prescribed the mifepristone by a non-physician and took the misoprostol at home, she would not encounter safety complications. That is not “arbitrary and capricious.”

Does the Fifth Circuit seriously think that all medicines should henceforth be taken off the market any time a plaintiff can show the FDA used the dreaded technique of inferential reasoning to assess their safety? Indeed, the FDA does this all the time. The FDA points out in its stay application that “routine biopsies were performed in trials for menopause hormonal therapy drugs to establish their safety, but FDA did not require biopsies in those drugs’ approved conditions of use.” Does this mean that the drugs are now illegal, or at least will be once a plaintiff-doctor comes forward saying he is stressed out about the prospect of seeing these women in the emergency room?

Three times in its decision, the Fifth Circuit cites FCC v. Prometheus Radio Project, 141 S. Ct. 1150, 1158 (2021). Prometheus confirms that an agency is allowed to make reasonable inferences from available data. In that case, the FCC changed certain ownership rules, based on the conclusion that the changes wouldn’t harm minority and female ownership. The plaintiffs said the FCC’s decision was based on insufficient data. The Supreme Court disagreed. It said:

To be sure, in assessing the effects on minority and female ownership, the FCC did not have perfect empirical or statistical data. Far from it. But that is not unusual in day-to-day agency decisionmaking within the Executive Branch. … In the absence of additional data from commenters, the FCC made a reasonable predictive judgment based on the evidence it had.

So I fail to see how Prometheus supports the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

Moreover, we now have an abundant body of data regarding the combined effects of all the safety changes. This has been the rule for the past seven years. No safety crisis has materialized. The plaintiffs certainly provide no evidence of any such crisis aside from the extremely vague anecdotes from the plaintiff-doctors’ declarations. Still, though, the Fifth Circuit holds that we have to immediately go back to 2016. The Fifth Circuit’s decision was scheduled to take effect within two days of its order (the Supreme Court has since entered a temporary administrative stay).

Consider, finally, the implications of the Fifth Circuit’s decision. The Fifth Circuit is requiring that the gestational age limit go back from 70 days to 49 days, before many women know they are pregnant. As noted above, I don’t think anyone, even the plaintiffs, has ever doubted the FDA’s conclusion that mifepristone works just as well at 70 days as at 49 days. But, too bad. So now, even in states where abortion is legal, women who decide to get an abortion from 49 days to 70 days are now forced to use a less effective drug regimen or get a surgical abortion. One gets the sense that perhaps “protecting women’s safety” was not actually motivating the Fifth Circuit here.

In-person requirement - FDA’s decision

In addition to finding that the FDA acted arbitrarily and capriciously in 2016, the Fifth Circuit also finds that the FDA acted arbitrarily and capriciously in 2021.

Prior to 2021, mifepristone was subject to an in-person dispensing requirement. In April 2021, the FDA decided that it would exercise its discretion not to enforce this requirement during COVID. In December 2021, the FDA concluded that in-person dispensing “is no longer necessary to assure the safe use of mifepristone.” The Fifth Circuit declared this conclusion arbitrary and capricious.

To understand this issue, it is necessary to explain one additional change the FDA made back in 2016.

When mifepristone was approved in 2000, the FDA required prescribers to report all serious adverse events—both fatal and non-fatal. In 2016, the FDA decided to require that, going forward, prescribers report only fatal events. The approving official reasoned: “After 15 years of reporting serious adverse events, the safety profile of Mifeprex is essentially unchanged. Therefore, I agree that reporting of labeled serious adverse events other than deaths can be collected in the periodic safety update reports and annual reports to the Agency.”

In the plaintiffs’ citizen petition challenging the FDA’s 2016 decision, the plaintiffs challenged the FDA’s decision not to require reporting of non-fatal serious adverse events. In its 2021 response, the FDA rejected that challenge. Here’s what the FDA said:

We acknowledge that there is always a possibility with any drug that some adverse events are not being reported, because reporting to the Agency’s MedWatch program by health care professionals and patients is voluntary. We do not agree, however, that the 2016 changes to the prescriber reporting requirements limit our ability to adequately monitor the safety of mifepristone for medical termination of pregnancy. Prior to the 2016 approval of the S-20 efficacy supplement, we assessed approximately 15 years of adverse event reports both from the Applicant and through the MedWatch program and determined that certain ongoing additional reporting requirements under the Mifeprex REMS, such as hospitalization and blood transfusions, were not warranted. This assessment was based on the well-characterized safety profile of Mifeprex, with known risks occurring rarely, along with the essentially unchanged safety profile of Mifeprex during this 15-year period of surveillance. Accordingly the Prescriber Agreement Form was amended as part of our 2016 approval of the S-290 efficacy supplement to require, with respect to adverse event reporting, only that prescribers report any cases of death to the Applicant.

We also note that the reporting changes to the Prescriber Agreement Form as part of our 2016 approval do not change the adverse event reporting requirements for the Applicants. Like all other holders of approved NDAs and ANDAs, the Applicants are required to report all adverse events, including serious adverse events, to FDA in accordance with the requirements set forth in FDA’s regulations. FDA also routinely reviews the safety information provided by the Applicants in the Annual Reports. As with all drugs, FDA continues to closely monitor the postmarketing safety data on mifepristone for the medical termination of pregnancy.

As noted above, in 2021, the FDA also concluded that in-person dispensing is no longer necessary to assure the safe use of mifepristone. In reaching that conclusion, the FDA relied on several sources of information:

FDA routinely monitors postmarketing safety data for approved drugs through adverse events reported to our FAERS database, through our review of published medical literature, and when appropriate, by requesting applicants submit summarized postmarketing data. For our recent review of the REMS, we searched our FAERS database, reviewed the published medical literature for postmarketing adverse event reports for mifepristone for medical termination of pregnancy, and requested that the Applicants submit a summary and analysis of certain adverse events.

(“FAERS” stands for FDA Adverse Event Reporting System.)

The FDA then walked through that information in exhaustive detail. First, the FDA analyzed events in the FAERS. Second, the FDA noted that it required the applicants to provide a summary and analysis of certain additional adverse events, and analyzed the summary that was provided. Based on that analysis, the FDA concluded that “there does not appear to be a difference in adverse events when in-person dispensing was and was not enforced and that mifepristone may be safely used without in-person dispensing.”

However, the FDA did not stop there. It then conducted a detailed, lengthy analysis study of the published literature on this topic. By my count, the FDA analyzed a total of 12 published studies: Aiken, Anger, Chong, Endler, Grossman, Hyland, Kerestes, Raymond, Reynolds-Wright, Rocca, Upadhyay, and Wiebe. After an exhaustive analysis of the findings and limitations of these studies, the FDA concluded that in-person dispensing is unnecessary.

In-person requirement - Fifth Circuit’s decision

The Fifth Circuit concludes that the FDA’s decision eliminating the in-person requirement was arbitrary and capricious. Here’s what the Fifth Circuit says:

Second, the 2016 Major REMS Changes eliminated the requirement that non-fatal adverse events must be reported to FDA. After eliminating that adverse-event reporting requirement, FDA turned around in 2021 and declared the absence of non-fatal adverse-event reports means mifepristone is “safe.” See, e.g., FDA Add. 861–76 (explaining that FDA’s FAERS database, which collates data on adverse events, indicated that the 2016 Major REMS Changes hadn’t raised “any new safety concerns”). This ostrich’s-head-in-the-sand approach is deeply troubling—especially on a record that, according to applicants’ own documents, necessitates a REMS program, a “Patient Agreement Form,” and a “Black Box” warning. See supra Part III.A. And it suggests FDA’s actions are well “outside the zone of reasonableness.” Prometheus, 141 S. Ct. at 1160. It’s unreasonable for an agency to eliminate a reporting requirement for a thing and then use the resulting absence of data to support its decision.

I’m going to assume that this paragraph is a reference to the FDA’s decision to change the in-person requirement (the only thing that changed after 2016). I’m not totally sure, as this paragraph doesn’t mention the in-person requirement. (An alternative interpretation of this paragraph is that the Fifth Circuit is offering a kind of preemptive strike against the FDA’s future reliance on any post-2016 data to refute the vague anecdotes offered by the plaintiff-doctors.)

But anyway, assuming this paragraph is a reference to the in-person requirement, the FDA didn’t adopt an “ostrich’s-head-in-the-sand approach.” Nor did it “eliminate a reporting requirement for a thing and then use the resulting absence of data to support its decision.”

As explained above, the FDA concluded in 2016 that prescribers no longer had to report non-fatal serious adverse events. However, the applicant still has to report adverse events. This is the general rule for all drugs. The Fifth Circuit could not have missed this, it is front and center in the FDA’s decision addressing the reporting requirement:

We also note that the reporting changes to the Prescriber Agreement Form as part of our 2016 approval do not change the adverse event reporting requirements for the Applicants. Like all other holders of approved NDAs and ANDAs, the Applicants are required to report all adverse events, including serious adverse events, to FDA in accordance with the requirements set forth in FDA’s regulations.

In addition, the FDA’s database also includes all adverse events—both fatal and non-fatal—voluntarily reported by prescribers, as well as all fatal adverse events mandatorily reported by prescribers.

So, the FDA reviewed all of this information. Why shouldn’t it review this? If it didn’t review it, that would be arbitrary and capricious.

But this wasn’t enough for the FDA, so it also solicited additional information from the applicant. This also wasn’t enough for the FDA, so it conducted an independent review of the Aiken, Anger, Chong, Endler, Grossman, Hyland, Kerestes, Raymond, Reynolds-Wright, Rocca, Upadhyay, and Wiebe studies.

This is not an “ostrich’s-head-in-the-sand approach.” The Fifth Circuit is banking on the hope that readers will be unaware of the FDA’s actual justifications for its actions.

To the extent the Fifth Circuit believes the FDA was arbitrary and capricious in altering the reporting requirement in 2016, it is simply wrong. Prescriber reporting of non-fatal events isn’t invariably necessary. It’s not required by statute. It’s not required for most drugs. This is purely within the FDA’s discretion. After 15 years, the FDA concluded it wasn’t necessary anymore. This was perfectly reasonable.

Indeed, the Fifth Circuit didn’t suggest there was anything arbitrary or capricious about this. But if that’s so, I can’t understand how the FDA could be attacked for relying on the adverse events database in 2021. If it’s not arbitrary and capricious for the FDA to relax the prescriber reporting requirement, then how can it be arbitrary and capricious for the FDA to rely on the reported data that exists (and other data) under the new prescriber reporting requirement?

The logical implication of the court’s decision is that, once the FDA altered the reporting requirement, it could never make any other change ever again, because by definition, the database lacked information that would have been reported under the prior reporting requirement. That cannot be right.

Generic mifepristone

The Fifth Circuit denied a stay with respect to the FDA’s 2019 approval of a generic version of mifepristone. It repeatedly made clear that it was doing this. (E.g., in the discussion of irreparable harm, the Fifth Circuit said: “The applicants make no arguments as to why the 2016 Major REMS Changes, the 2019 Generic Approval, or the 2021 and 2023 Mail Order Decisions are similarly critical to the public even though they were on notice of plaintiffs’ alternative requests for relief.”)

The Fifth Circuit gave no reason for this. Literally nothing.

It couldn’t have implicitly approved the district court’s reasoning. The district court’s sole basis for overturning the 2019 approval of generic mifepristone was its decisions with respect to the 2000 approval and 2016 changes. But with respect to branded mifepristone, the Fifth Circuit stayed the district court’s decision overturning the 2000 approval. It merely returned branded mifepristone to the pre-2016 regime. Therefore, at most, it should have required generic mifepristone also to be subject to the pre-2016 regime.

Instead the Fifth Circuit declared generic mifepristone illegal. No one knows why, but we must obey.

**

We will see what the Supreme Court does next week.

Have we crossed the threshold-- in terms of the number of bad-faith arguments, willful misreadings of the record, and flat-out factual lies-- where we can yet say that this opinion is judicial misconduct? Because I am really struggling to see how anything could ever be judicial misconduct if this is not.

Your discussions on these rulings are outstanding.