Does standing follow the merits?

Often. Not always.

Plaintiffs cannot bring lawsuits in federal court unless they have standing. To establish standing, the plaintiff must demonstrate a concrete and particularized injury, caused by the defendant, that would be redressed by the sought-after relief.

It may seem odd to non-lawyers that plaintiffs without standing would file lawsuits. If the plaintiff wasn’t injured or wouldn’t benefit from the litigation, why would it go through the trouble of litigating? The answer is, many plaintiffs have motives for bringing lawsuits that go beyond the specific relief they’re seeking from the court. For example, plaintiffs may be pursuing a philosophical goal. But philosophy isn’t enough to get a plaintiff into federal court. The plaintiff must show a concrete stake in the specific dispute being litigated.

In the Supreme Court, it is common for controversial cases to feature hot-button merits issues combined with unrelated, mundane standing disputes. The student-loan cases currently pending before the Court are a good example. Several plaintiffs, including the state of Missouri, filed lawsuits contending that President Biden’s partial forgiveness of student loan debt violated federal law. This is a juicy, consequential issue which will likely divide the Court along typical ideological lines. But before the Court can decide this question, it must decide whether the plaintiffs have standing. The plaintiffs have various theories of standing, but the most promising seems to be that the student-loan plan will harm the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority (MOHELA) and that an injury to MOHELA counts as an injury to Missouri. The Justice Department contends that MOHELA’s injury doesn’t qualify as an injury to Missouri because MOHELA is a legally separate entity that declined to sue. Missouri retorts that MOHELA really isn’t that separate from Missouri. This is an extremely obscure and random issue that turns on esoteric intricacies of Missouri law.

In principle, the Justices’ view of the merits of the student-loan dispute shouldn’t affect their view of the antecedent question of standing. The Court isn’t even allowed to get to the merits question until it determines that the plaintiffs have standing. Also, there’s no particular reason that the Justices’ views of the merits would track their views of MOHELA’s standing. I have no idea whether it is a judicially conservative or progressive position to say that MOHELA does or does not have standing. So, in a perfect world, we’ll see no correlation between the Justices’ view of standing and their view of the merits. (We’ll find out soon.)

Alas, the world is not always perfect. Judges have been known to let their views of the merits influence their assessment of antecedent procedural issues such as standing. This was one of the troubling things about the mifepristone litigation in Texas. It seemed that the Fifth Circuit and Northern District of Texas’s strong views on the merits influenced them to take an unusually broad view of Article III standing.

Does the Supreme Court do the same thing? I decided to check.

(DALL-E on “standing.” Yep, they’re definitely standing.)

My methodology was as follows:

I searched for “Article III” in Westlaw for cases going back ten years (to the start of 2013). I chose ten years because it seemed like a nice round number and I didn’t want too many cases on my hands.

I filtered out all cases in which an issue of Article III standing was litigated, and the plaintiff seemed to be either conservative or progressive. Usually the classification was pretty easy (gun owners are conservative, abortion doctors are progressive). In class-action or collective-action cases, I classified the plaintiffs as progressive, because the real parties in interest are class-action lawyers, who rival Oberlin professors as the most Democratic-leaning constituency in America.

I took the cases in which the Supreme Court divided on standing—that is, some Justices thought there was standing, and others thought there wasn’t. There were a lot of cases in which a litigant threw up a Hail Mary argument on standing, and either the Court unanimously rejected it or the majority rejected it and the dissent didn’t talk about it. Many of these featured conservative plaintiffs (e.g., West Virginia v. EPA, FEC v. Cruz, Seila Law v. CFPB, Janus v. AFSCME), although a couple featured progressive plaintiffs (e.g., Department of Commerce v. New York). Last week’s oral argument in Tyler v. Hennepin County, in which the County made the intriguing argument that Ms. Tyler lacked standing to challenge the seizure of thousands of dollars of her home equity, is the finest example of this phenomenon I have yet seen. I didn’t count these cases because I didn’t consider them relevant to the purpose of this exercise, which was to assess whether judges’ view of standing in close cases was affected by the merits.

I tallied the Justices’ votes in each of these cases. I would only count a vote if the Justice actually took a position on standing in the case. If the Justice was silent on standing, it didn’t count.

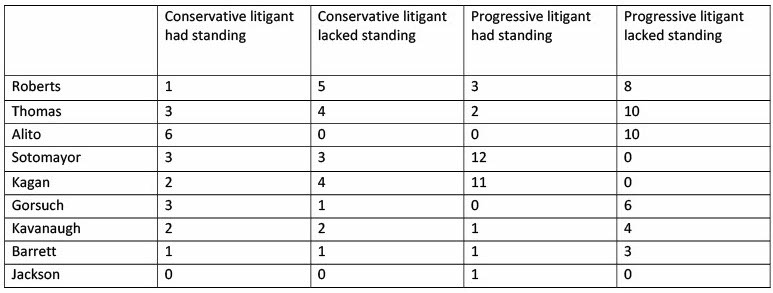

I made a chart of the number of votes the Justices cast for and against standing in cases with conservative litigants, and in cases with progressive litigants. That’s it. No whiz-bang correlation coefficients.

I realize there are lots of methodological flaws here. Small sample size, sometimes the standing questions are interlinked with the merits questions, etc. Folks, I’m just a country lawyer with a country Substack. I know there are some tenured law professors reading this, I am sure y’all can do a better job.

Here are the cases I found. Counting votes frequently involved judgment calls. In some cases I have included pedantic footnotes explaining how I tallied the votes, which I encourage readers to skip. After listing the cases, I will show a chart with the results, and then offer some commentary.

Conservative litigants

California v. Texas, 141 S. Ct. 2104 (2021).

Plaintiffs: Various states and individuals

Merits argument: The Affordable Care Act is unconstitutional and should be invalidated in its entirety

Standing question: Do the plaintiffs have standing to challenge the $0 individual mandate?

Holding: No standing (7-2)

Uzuegbunam v. Preczewski, 141 S. Ct. 792 (2021).

Plaintiffs: Evangelical Christians who sought to distribute religious literature on college campus

Merits argument: Their First Amendment rights were violated when they were prevented from distributing religious literature

Standing question: Is a request for nominal damages enough for standing?

Holding: Yes, there is standing (8-1)

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. City of New York, 140 S. Ct. 1525 (2020).

Plaintiff: Gun rights organization

Merits argument: New York gun law violates the Second Amendment

Standing question: Did New York’s repeal of the law moot the case?

Holding: The case is moot (6-3)

Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, 139 S. Ct. 1945 (2019).

Litigant seeking standing: Republican-controlled Virginia House of Delegates, which sought standing to appeal to Supreme Court

Merits argument: District court should have upheld pro-Republican gerrymander

Standing question: Does the House of Delegates have standing to appeal when Virginia’s Attorney General chose not to appeal?

Holding: No standing (5-4)

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, 576 U.S. 787 (2015).

Plaintiff: Republican-controlled legislature

Merits argument: Arizona voter initiative that delegated redistricting to an independent redistricting commission is unconstitutional.

Standing question: Does the legislature have standing to bring this claim?

Holding: Yes, there is standing (5-2, 2 Justices didn't opine on this issue); the legislature lost on the merits (5-4).1

United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (2013).

Litigant seeking standing: Republican-controlled House of Representatives’ Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group (BLAG).

Merits argument: The Defense of Marriage Act is constitutional.

Standing question: Does BLAG have standing to defend DOMA?

Holding: 3 Justices said BLAG lacked standing, one Justice said it had standing, five Justices did not reach this question; on the merits, the Supreme Court struck down DOMA (5-4).2

Hollingsworth v. Perry, 570 U.S. 693 (2013).

Litigant seeking standing: Proponents of Proposition 8 (California proposition defining marriage as between one man and one woman)

Merits argument: Proposition 8 is constitutional

Standing question: Do official proponents of ballot initiative have standing to defend constitutionality of ballot initiative?

Holding: No standing (5-4)

Progressive litigants

Reed v. Goertz, 143 S. Ct. 955 (2023).

Plaintiff: Death row inmate

Merits argument: Lawsuit challenging dismissal of lawsuit regarding DNA testing is timely

Standing question: Does inmate have standing to sue the District Attorney?

Holding: Yes, plaintiff has standing (6-1, 2 Justices didn’t opine on this issue).3

Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, 142 S. Ct. 522 (2021) / In re Whole Woman’s Health, 142 S. Ct. 701 (2022).

Plaintiffs: Abortion doctors

Merits argument: Texas’s anti-abortion statute is unconstitutional

Standing question: Do the doctors have standing to sue the various defendants (judges, clerks of court, licensing officials, private citizens)?

Holding: Debatable, but I think it’s fairest to call this one 5-4 in favor of no standing (see footnote for details).4

TransUnion v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190 (2021).

Plaintiff: Class action

Merits argument: TransUnion violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act

Standing question: Do class members have standing based on allegations of risk of harm, even when no harm materialized?

Holding: No standing (5-4)

Trump v. New York, 141 S. Ct. 530 (2020).

Plaintiff: New York

Merits argument: Trump administration shouldn’t be allowed to exclude undocumented non-citizens from census count

Standing question: Was lawsuit premature when it wasn’t clear what the Trump administration would do?

Holding: No standing (6-3)

June Medical Services v. Russo, 140 S. Ct. 2103 (2020).

Plaintiffs: Abortion doctors

Merits argument: Louisiana abortion statute violated constitutional right to an abortion

Standing question: Do abortion doctors have standing to pursue interests of their patients?

Holding: Yes, there is standing (5-3, with 1 Justice not voting on standing); Court struck down law on the merits (5-4).5

Thole v. U.S. Bank, 140 S. Ct. 1615 (2020).

Plaintiffs: Class action

Merits argument: Defendants violated ERISA

Standing question: Can unharmed plaintiffs sue based on analogy to the law of trusts?

Holding: No standing (5-4)

American Legion v. American Humanist Association, 139 S. Ct. 2067 (2019).

Plaintiff: Secular organization

Merits argument: Display of cross violates Establishment Clause

Standing question: Do offended observers of cross have standing?

Holding: Two Justices found standing, two said no standing, Establishment Clause claim was rejected by a 7-2 vote.6

Campbell-Ewald v. Gomez, 577 U.S. 153 (2016).

Plaintiffs: Class action

Merits argument: Class members are entitled to damages for receiving unwanted text message

Standing question: Does the plaintiff have standing to pursue the class action if the defendant offers to satisfy the plaintiff’s claim, even if the plaintiff says no?

Holding: Yes, there is standing (6-3); the defendant’s merits argument was also rejected.

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, 575 U.S. 254 (2015).

Plaintiff: Alabama Legislative Black Caucus

Merits argument: Alabama legislature drew an illegal gerrymander that favored Republicans

Standing question: Did the plaintiff submit sufficient evidence of standing?

Holding: The plaintiffs included evidence of standing in a Supreme Court lodging, so they should be able to submit this evidence in the district court (5-4); the plaintiffs also got some relief on the merits (5-4).7

United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (2013).

Litigant: Justice Department

Merits argument: Defense of Marriage Act is unconstitutional

Standing question: Can the Justice Department ask the Supreme Court to grant certiorari and affirm a lower-court determination that DOMA is unconstitutional?

Holding: Yes, there is standing (5-4); the Court also held that DOMA is unconstitutional (5-4).

Genesis Healthcare Corp. v. Symczyk, 569 U.S. 66 (2013).

Litigant: Employees suing in wage-and-hour collective action

Merits argument: Employer violated Fair Labor Standards Act

Standing question: Can a plaintiff pursue a collective action when her individual claim is moot?

Holding: No standing (5-4)

Clapper v. Amnesty International USA, 568 U.S. 398 (2013).

Litigant: Civil rights organizations who seek to talk with foreigners that the U.S. government wants to surveil

Merits argument: The surveillance is unconstitutional

Standing question: Do the plaintiffs have standing when they can’t prove that the U.S. government will surveil their particular calls?

Holding: No standing (5-4)

I prepared a table summarizing the Justices’ votes, which is below. Sorry about the hideous .JPG, Substack doesn’t support tables. For those interested I’ve included a PDF at the bottom for download with a summary of the results for all Justices during the relevant time period as well as a chart of case-by-case results.

My takeaway:

There is clearly some correlation between the Justices’ view of the merits and their view of standing. For instance, compare New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. City of New York, 140 S. Ct. 1525 (2020) with Trump v. New York, 141 S. Ct. 530 (2020). In the former case, the Court held that New York’s repeal of the challenged gun law mooted the case, with three conservative-leaning Justices (Gorsuch, Alito, and Thomas) dissenting. In the latter case, the Court held that New York’s challenge to the Trump administration’s plans for the census was unripe, with three progressive-leaning Justices (Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan) dissenting. It is perhaps not a coincidence that Justices Gorsuch, Alito, and Thomas supported the Second Amendment challenge to the gun law, and Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan supported New York’s challenge regarding the census. As a standing hawk myself, I think that neither case presented an Article III case or controversy, but only two Justices (Roberts and Kavanaugh) took that view.

That said, there are several notable examples of the Justices voting against type on standing, including in high-profile cases.

One outstanding example is Hollingsworth v. Perry, 570 U.S. 693 (2013). In that case, a federal district court struck down Proposition 8, California’s ballot initiative that defined marriage as between a man and a woman. California declined to appeal that decision, so the official proponents of Proposition 8 (i.e., opponents of same-sex marriage) attempted to step in to defend it on appeal. If they lacked standing to appeal, the district court’s decision would stand, and same-sex marriage would become legal across California.

The Supreme Court held, by a 5-4 vote, that the proponents lacked standing. Chief Justice Roberts—who would later vigorously dissent in Obergefell (which legalized same-sex marriage nationwide)—wrote the opinion for the Court. Notably, among the Justices who joined the opinion was Justice Scalia. Justice Scalia, to put it mildly, disagreed with the view that Proposition 8 was unconstitutional. But, as would be expected from one of the greatest Supreme Court Justices ever, he was incredibly principled and there was zero chance he’d let his view of the merits influence his vote on standing. So he cast the deciding vote legalizing same-sex marriage across California. Meanwhile, among the dissenters was Justice Sotomayor. I’m sure she disagreed with the legal position of the Proposition 8 proponents as strongly as Justice Scalia agreed with it, but she historically has adopted a broad view of standing and she concluded that the Proposition 8 proponents had a right to their day in court, so that’s how she voted.

Another striking example is Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, 139 S. Ct. 1945 (2019). The plaintiffs challenged Republican-drawn district maps as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. A federal district court ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor and ordered the maps to be redrawn. The Attorney General, a Democrat, declined to appeal. So, the House of Delegates, controlled by Republicans, attempted to appeal instead. If the House of Delegates lacked standing to appeal, the district court’s decision redrawing the maps would stand.

The Supreme Court held, by a 5-4 vote, that the House of Delegates lacked standing. Justice Ginsburg wrote the opinion for the Court, but among the votes in the majority were Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch. I am 100% sure that both Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch disagreed with the district court’s decision striking down the Republican-drawn map. I also strongly suspect they would have preferred that Republicans control the Virginia legislature. But they thought there was no standing, so they joined Justice Ginsburg’s opinion. A couple of months after this decision, the Virginia House of Delegates swung from Republican to Democratic control, so Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch might have cast the deciding votes to hand control of the Virginia legislature to the Democrats. Meanwhile, Justice Breyer dissented in the case, effectively voting to hand political power in Virginia to Republicans.

Justice Thomas, in particular, has cast multiple votes on standing, in both directions, in a manner opposite to his presumed view of the merits. Bethune-Hill is one example. Another example is California v. Texas, 141 S. Ct. 2104 (2021). After Justice Barrett joined the Court, there was widespread speculation that finally, there were five votes to invalidate the Affordable Care Act. Texas brought a lawsuit saying that the 0$ individual mandate was unconstitutional and inseverable from the rest of the Affordable Care Act, so the whole Act had to be struck down. A federal district court bought this argument, and the case ultimately reached the Supreme Court. The Court, per Justice Breyer, held that the plaintiffs lacked standing. Justice Thomas joined Justice Breyer’s opinion and wrote a concurring opinion reiterating his antipathy for the Affordable Care Act but observing that “whatever the Act’s dubious history in this Court, we must assess the current suit on its own terms.”

Justice Thomas also voted to hold that the Republican-controlled Arizona State Legislature lacked standing to challenge the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, even though the effect of this vote would have been to shift the balance of power in Arizona from Republicans to Democrats. Meanwhile, while I doubt that Justice Thomas has warm feelings towards class-action lawyers, he voted with the Court’s Democratic appointees in favor of standing for class-action plaintiffs in two significant cases, TransUnion v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190 (2021) and Campbell-Ewald v. Gomez, 577 U.S. 153 (2016).

The Chief Justice’s votes on standing appear totally uncorrelated with his views of the merits. On eight separate occasions he’s either voted that a conservative litigant lacks standing or a progressive litigant has standing, even though the standing issue was difficult enough to divide the Court.

Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh have also cast multiple such votes in their short tenure on the Court. Both of them voted against standing in California v. Texas and for standing in Reed v. Goertz. Justice Kavanaugh also voted against standing in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. City of New York, even though there’s little doubt he thought the gun law at issue was unconstitutional.

I’d like to raise one other example that is not specifically about standing, but illustrates a similar phenomenon. Last Term, the Supreme Court heard two cases about whether Republican state officials had a procedural right to intervene to defend state laws. Cameron v. EMW Women’s Surgical Center, P.S.C., 142 S. Ct. 1002 (2022), addressed whether Kentucky’s Attorney General could intervene to defend a Kentucky abortion law, while Berger v. North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, 142 S. Ct. 2191 (2022) addressed whether North Carolina’s legislative leaders could intervene to defend a North Carolina Voter ID statute. In both cases, Justice Kagan and Justice Breyer joined majority opinions saying that the officials could intervene, even though this would have the practical effect of improving the chances that those laws would survive in court.

On balance, I think there is reason to be optimistic that the Court is deciding questions of standing in a principled way. The Court’s vote on the mifepristone stay reflects this dynamic.

That’s enough for today! Next week’s post will be entitled: “Why does doctrine get so complicated? (Or does it?)”

Five Justices said there was standing; two (Justices Scalia and Thomas) said there wasn’t standing; the other two (Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito) were silent on standing and dissented on the merits. Presumably Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito would have had to conclude that the legislature had standing in order to cast a vote in its favor on the merits. Still, I stuck with my rule that if the Justice was silent, it didn’t count.

In Windsor, there were two different standing disputes. One involved whether the Obama Justice Department—which was urging the Supreme Court to invalidate DOMA—had standing to seek Supreme Court review. The other involved whether BLAG—which was urging the Supreme Court to uphold DOMA—had standing to intervene in DOMA’s defense. In my tally, I counted both votes. I counted the Justice Department as a progressive litigant and BLAG as a conservative litigant.

Justice Thomas said there wasn’t standing. Justices Alito and Gorsuch said the suit was time-barred and didn’t talk about standing. Arguably, Justices Alito and Gorsuch would have had to find standing in order to address the timeliness issue. But maybe not; this was a dissent, so there was no requirement that they opine on every issue in the case. I stuck to my rule that if a Justice is silent, it doesn’t count.

The portion of the opinion addressing whether the plaintiffs had standing to sue the clerks was definitely 5-4 in favor of no standing. The Court’s decision appeared, at least to me, to hold (by an 8-1 margin) that the plaintiffs did have standing to sue certain Texas executive officials, at least at the motion to dismiss stage. However, on remand, the Fifth Circuit interpreted the Court’s discussion of this issue to be a merely tentative suggestion that there might be standing, and certified the issue to the Texas Supreme Court. The plaintiffs petitioned for a writ of mandamus in the Supreme Court, saying that the Fifth Circuit misunderstood the Supreme Court’s mandate, but the Supreme Court denied the petition by a 6-3 vote (with all 5 Justices in the majority on the clerks issue voting to deny). The Texas Supreme Court ultimately held that the officials lacked enforcement authority, meaning that there wasn’t standing. So the ultimate conclusion was that the plaintiffs lacked standing to sue anyone. In view of the Court’s denial of the mandamus petition, I think it’s fairest to characterize this one as 5-4 for no standing.

This was another tricky one to tally. 5 Justices definitely said there was standing. Justice Thomas’s dissent said there was no third-party standing, and hence no standing under Article III. Justices Alito and Gorsuch dissented on third-party standing without specifying whether their position was grounded in Article III; Justice Thomas joined this portion of their dissent. Ultimately, saying “no third-party standing,” without specifying whether this is an Article III issue or not, is close enough to saying “no standing” that for purposes of this exercise, I counted Justice Alito and Justice Gorsuch’s votes in the no-standing column.

Justice Thomas and Gorsuch said there was no standing. The majority opinion by Justice Alito was completely silent on this issue. The dissent (Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor) included a footnote declaring itself troubled by the no-standing position, which I felt was sufficient to say that they found standing.

This one was a bit messy, as the Justices in the majority merely said that the plaintiffs get to put in more evidence. But there were 5 votes to vacate on standing and 4 votes to affirm, in a highly political case, so I felt this one was reasonable to count.

Further evidence that Alito is an unprincipled, radical, outcome determinative hack.

"I’m just a country lawyer with a country Substack....."

Adam Unikowsky, everybody! He plays to the kids.... But he'll be here all week. And don't forget to tip your server...........