Trust the ichthyologists

But verify.

The Trump Administration will no doubt bring us some intriguing legal developments. But it’s still early. So today’s post will instead discuss a 47-year-old Supreme Court case about a fish. Please don’t unsubscribe.

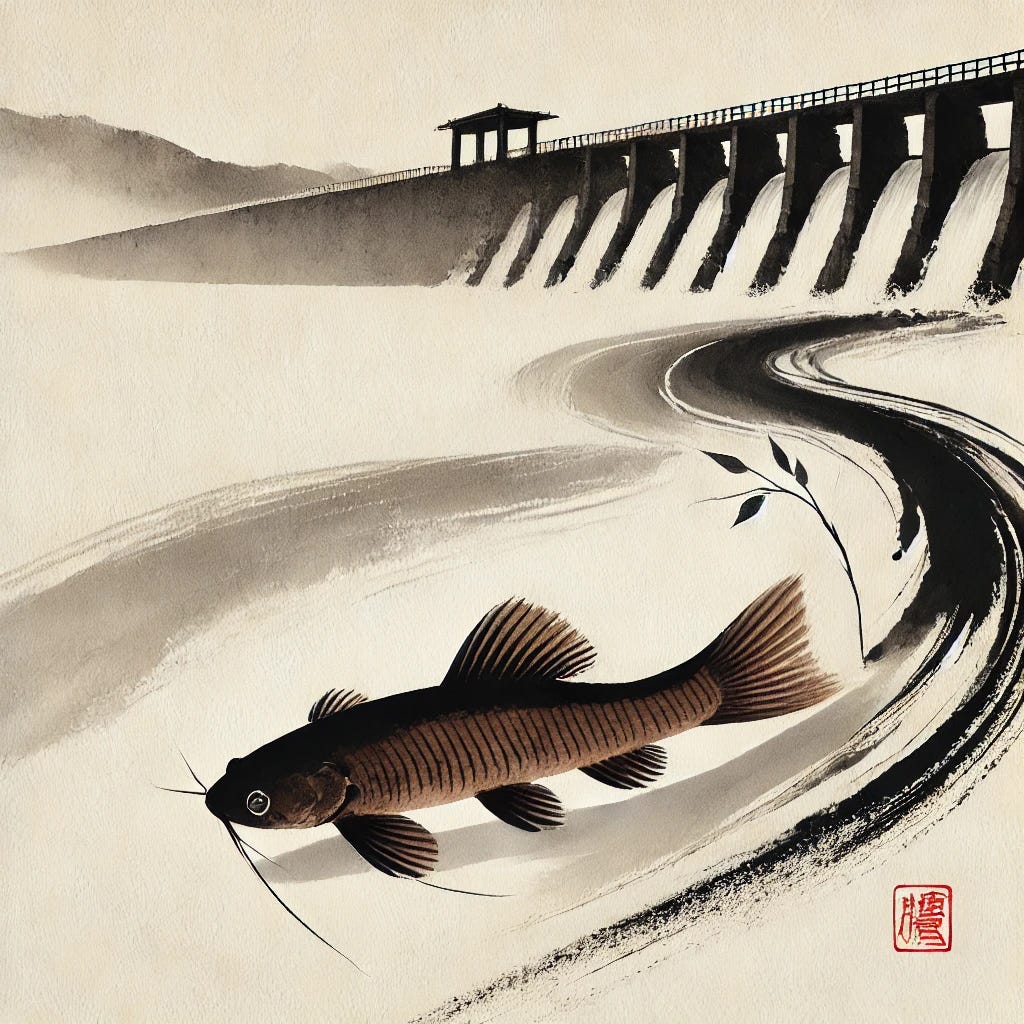

Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978), is probably the most famous Supreme Court environmental law case ever. In Hill, the Supreme Court held that construction of the Tellico Dam in Tennessee—which was over 80% complete—had to be halted under the Endangered Species Act to protect a recently-discovered fish species known as the snail darter. Hill remains a staple of both the environmental law and statutory interpretation curricula.

Recently, the New York Times reported on a new study revealing that the snail darter isn’t a species after all. Instead, it is an eastern population of a different fish known as the stargazing darter, which is not endangered. So the whole epic struggle was premised on a scientific mistake.

Whoa! If you know me, you know this is the sort of story that would make me a little bit obsessed. So I dug into this. I relied on the following sources:

The original article recognizing the snail darter: David A. Etnier, Percina (Imostoma) Tanasi, A new percid fish from the little Tennessee River, Tennessee, Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington (Jan. 22, 1976).

The new study: Ava Ghezelayagh et al., Comparative species delimitation of a biological conservation icon, Current Biology (2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.11.053 .

Although Dr. Ghezelayagh’s article is clearly written, there were a few aspects of her methodology I didn’t fully understand. So, I emailed her with some pedantic questions and quickly received a detailed and thorough response. I’m very grateful to Dr. Ghezelayagh for this, it’s pretty awesome that a scientist would respond to a random lay person’s cold email about her academic work.

Finally, this post would not have been possible without AI. You can upload the article to Claude and ask questions like “I don’t understand the chart on page 5, what are the red rectangles and blue rectangles” and it will explain it to you until you understand. It’s like having an infinitely patient person with a Ph.D. in all subjects sitting next to you. To the autodidacts of the world, this is truly the greatest technology in human history.

Here are my takeaways:

This is mostly a heartwarming story about science getting better. It was reasonable for Dr. Etnier to conclude in 1976 that the snail darter was a new species. Dr. Ghezelayagh’s study vindicates many of Dr. Etnier’s findings and reaches a different conclusion from Dr. Etnier based on new technology that would have been unthinkable in 1976.

That said, this case does illustrate how law can influence science. If scientists know that categorizing an animal population as a “species” will halt a construction project that they support or oppose, then they have an incentive to shade their analysis accordingly.

Structuring the administrative state to distinguish good science from bad science is a notoriously difficult problem, but the situation is much better now than it was in 1976.

Wedding bells

In 1973, Congress enacted the Endangered Species Act. Here’s what it says: “Each federal agency shall … insure that any action authorized, funded, or carried out by such agency … is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species or threatened species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of habitat of such species which is determined … to be critical.”

OK, so the Endangered Species Act protects endangered “species.” What’s a “species”?

There’s actually no clear definition. Intuitively, one would think it means something like: “if you put a male and female fish in a tank, and wedding bells ring, they’re the same species.” But for several reasons, it’s more complicated than that.

First, sometimes distinct animal populations form a chain, in which adjacent populations can interbreed but the populations at each end of the chain can’t interbreed with each other—a so-called “ring species.”

This phenomenon makes it challenging to decide the metes and bounds of a “species” for Endangered Species Act purposes. Suppose you have three populations of animals—A, B, and C. A and C are both endangered, but B is abundant. A can interbreed with B, and C can interbreed with B, but A and C can’t interbreed with each other. Are A and C “endangered species”? A developer would say: “no, A is the same species as B and C is the same species as B, so why are we stopping the project?” An environmentalist would retort: “If A is the same species as B, and C is the same species as B, this would imply that A is the same species as C, but that’s wrong because A and C can’t interbreed!” There’s no perfectly satisfactory definition of a “species” in this situation.

Second, sometimes animals are different enough from one another that they’re widely considered to be separate species, even though they can, in principle, interbreed. Polar bears and grizzly bears occasionally cross paths and bear fertile offspring; does this mean that they’re not separate species? Saying “it’s OK to let the grizzly bear go extinct because polar bears also exist” seems contrary to Congress’s purpose in enacting the Endangered Species Act. As another example, humans and Neanderthals are generally considered separate species even though they interbred from time to time.

Third, conversely, sometimes two populations of animals are sufficiently similar that they are considered the same species, even if they’re geographically isolated and therefore don’t, as a practical matter, interbreed. Or maybe they just don’t want to interbreed. Experience has taught that humans can occasionally be picky, and the same is true of our fellow animals.

To make matters more complicated, the Endangered Species Act defines “species” to include “any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, and any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature.” So even if a particular group of fish doesn’t form its own “species,” it’s still protected if it forms a “subspecies” or “distinct population segment.” These terms also lead to difficult line-drawing problems.

Eureka!

In the 1960s, the Tennessee Valley Authority decided to build a dam on the Little Tennessee River known as the Tellico Dam. This wasn’t a dam for purposes of generating electricity. Its purpose was to create a big man-made reservoir (“Tellico Lake”) for purposes of stimulating tourism.

Building Tellico Dam would have the effect of wiping out the lower portion of the Little Tennessee River. In 1973, Tennessee’s leading ichthyologist, Dr. David Etnier, decided to check out the local fish population before their day of doom. And he spotted a funny-looking brown fish that was approximately 3 inches long.

That discovery took on new significance a few months later, when Congress enacted the Endangered Species Act. Congress undoubtedly had charismatic species in mind like whooping cranes and grizzly bears. But God in His wisdom chose to create uninspiring animals too. And, as far as Dr. Etnier was aware, this particular fish was found only in that particular stretch of the Little Tennessee River. If Tellico Dam was built, the hapless snail darter (so named because it eats snails) would go extinct.

In 1976, Dr. Etnier published his legendary article recognizing the snail darter as a new species. Here is how the article describes the fateful discovery:

Robert A. Stiles and I visited the river at Coytee Spring, River Mile 7, Loudon County, Tennessee, on 12 August 1973, in an attempt to survey the fish fauna with the aid of face masks and snorkels. Although very few fishes were seen, a single specimen of a very unusual darter was observed and “scooped up” by hand by the author.

Now that’s science! Dr. Etnier took a close look at this very unusual darter and concluded it was a new species.

How did he reach this conclusion? Modern genetic analysis didn’t exist in 1976, so Dr. Etnier’s methodology consisted of collecting a bunch of snail darters, taking measurements, and deciding that the snail darter looks different enough from all other darters to be its own species. It’s the type of article that could have been written in 1776.

Dr. Etnier acknowledged that the snail darter, Percina tanasi, is pretty similar to the stargazing darter, Percina uranidea, which is found in nearby rivers. But he concluded that the snail darter “differs from known populations of P. uranidea in body width, paired fin length, saddle width, nuptial tubercle pattern, several aspects of pigmentation, number of anal and caudal fin rays, and probably vertebral number.” The most striking difference between the two species was their anal fin ray counts: most of the snail darters he found had 12 anal fin rays (though some had 11), while most of the stargazing darters he found had 11 anal fin rays (though some had 12).

In scientific significance, this discovery wasn’t exactly the discovery of the coelacanth. The Supreme Court’s opinion notes that there were 130 known darters at the time, 8 to 10 of which were identified in the preceding five years. It seems we are now up to approximately 248 different darter species.

Still, as far as the Endangered Species Act is concerned, all darter species are sacred. Local citizens petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to list the snail darter as an endangered species, and the Fish and Wildlife Service complied.

The Federal Register notice finding the snail darter to be an endangered species is, to the modern eye, an interesting read. The agency said that sixteen comments were received. Twelve commenters supported the listing of the snail darter as an endangered species. Three commenters offered views that were dryly described as not “relevant to the biological evaluation.” The final commenter was the Tennessee Valley Authority—the agency that was building the dam. The TVA didn’t exactly argue that the snail darter wasn’t a new species, but instead said that there wasn’t enough information to make that assessment, and that it really, really wanted to complete the dam.

The Fish and Wildlife Service said, in essence, that Dr. Etnier published an article describing the snail darter as a new species, and there was no contrary research, so whaddaya gonna do? Argue with Tennessee’s leading ichthyologist? If this had come up today, there would have been hundreds of comments on both sides, many AI-generated. The 1970s were a gentler time, I guess. Given the record before it, it’s hard to blame the Fish and Wildlife Service for agreeing with Dr. Etnier that the snail darter is a new species.

And the rest is history. Opponents of the Tellico Dam sued the TVA, alleging that the dam would jeopardize the snail darter’s continued existence. If you believe Dr. Etnier that the snail darter is a distinct species that lives only in this specific stretch of river, that was undeniably true. The TVA argued that it was absurd to halt the construction of a dam that was 80% complete to save this obscure and inglorious fish. But, the Supreme Court held, the law is the law.

Congress later stepped in to override the Supreme Court’s decision and ensure that the dam would be completed. The reservoir created by the dam— Tellico Lake—now exists. Based on the YouTube video touting it, I would characterize it as moderately scenic. Meanwhile, the snail darter has been found in nearby rivers, so all’s well that ends well.

Caveman genius

Fast forward 40 years.

Dr. Ghezelayagh’s article concludes that the snail darter is the same species as the stargazing darter.

Dr. Ghezelayagh takes samples of DNA sequences from 249 snail darters and 81 stargazing darters. The stargazing darters are drawn from two populations, one in the White River in Missouri and Arkansas and one in the Ouachita River in Arkansas. Figure 2 of the article depicts the results in a phylogenomic tree (a diagram that shows biological relationships between animals by comparing their DNA).

The phylogenetic tree reveals that snail darters (red branches) and the two groups of stargazing darters (blue branches) are indeed genetically distinct from one another: according to the paper, “three major lineages are resolved with strong node support across a variety of data filtering thresholds and methods: all sampled snail darter specimens, stargazing darters from the White River system in Arkansas and Missouri, and stargazing darters from the Ouachita River system in Arkansas.” But there are “extremely short branch lengths,” meaning that the distinctions among these groups are small. Also, even though the two groups of stargazing darters are generally considered a single species, they’re about as far apart from each other as they are from the snail darter.

I come away from this analysis extremely impressed with Dr. Etnier’s work. To be sure, in terms of level of sophistication, Dr. Ghezelayagh’s article makes Dr. Etnier’s article look like it came from the Paleolithic era. Dr. Ghezelayagh conducts an elaborate genomic analysis; Dr. Etnier scoops up a fish and measures it with a ruler. But Dr. Ghezelayagh’s work also makes Dr. Etnier look like a kind of caveman genius. Of all the 100+ darters, Dr. Etnier immediately recognized that the snail darter was closest to the stargazing darter merely by examining it and watching it wriggle. Also, Dr. Etnier is aware of the separate population of Ouachita River darters. He’s agnostic as to whether they’re a separate species from the White River darters but concludes: “The observable differences between these sympatric species (not recognized by modern ichthyologists as being distinct until 1970) are similar in magnitude to those between P. uranidea and P. tanasi.” And that’s exactly what the genomic analysis shows!

IDK, to me you have to be a fish genius to figure out these genetic relationships from just staring at the fish when there are 100+ darter species out there. To me a minnow is a minnow. Maybe this is obvious to an ichthyologist but I cannot imagine myself memorizing subtle differences among 100 types of darters.

Anyway, Dr. Ghezelayagh nonetheless concludes that snail darters are just a subpopulation of stargazing darters. She reaches that conclusion in a clever way. She takes 12 pairs of darter sister species—that is, pairs of darter species more similar to each other than to any other darter species, but still widely recognized as separate species—and compares how divergent they are using a genomic analysis. She finds that there is much greater genomic divergence between each of those 12 reference pairs than between the snail darter and stargazing darter. Therefore, she concludes, “the level of genetic divergence between the Snail Darter and Stargazing Darter is more consistent with population-level differences than differences between distinct species.”

From my perspective as a lawyer, this analysis makes sense. Congress didn’t have any particular technical definition of “species” in mind when it enacted the Endangered Species Act. Instead Congress meant something like: “a population of animals that is different enough from other populations that scientists would consider the population to be a separate ‘species,’ according to the way scientists conventionally use that term.” And Dr. Ghezelayagh’s method is consistent with that interpretation. She identifies pairs of darters that are considered to be closely related but nonetheless distinct species, and concludes that the degree of divergence among those pairs marks the dividing line between “distinct species” and “distinct populations.” Obviously there will be some grey areas, but the paper persuasively explains that the snail darter/stargazing darter pair isn’t in that grey area—it’s firmly in distinct-population zone.

The New York Times article implies that Dr. Etnier distorted his findings in order to impede the Tellico Dam and that the new study debunks Dr. Etnier’s work. I don’t know what was going through Dr. Etnier’s mind, but that’s the wrong take. Dr. Ghezelayagh frames her study as presenting a new protocol for determining whether a population is a “species,” not as calling out an error by Dr. Etnier. Also, none of the sophisticated technological tools she relies upon were available when Dr. Etnier’s article was published. It’s not clear Dr. Etnier even used a computer in writing his article. It’s like comparing Pong—the state-of-the-art game when the snail darter was discovered—and Elden Ring.

You may be wondering: the Endangered Species Act deems “subspecies” and “distinct population groups” to be distinct “species,” at least as far as fish are concerned. Might the snail darter be a “subspecies” or “distinct population group” and therefore entitled to protection even if it’s not a separate “species”? The study doesn’t express a view on this: “It is not clear if the level of distinctiveness of the Snail Darter would merit protection as either a subspecies or DPS.” So, the study actually doesn’t take a position on whether TVA v. Hill should have come out the other way.

(Incidentally, the New York Times article is way off on this. It says the study reports that “the snail darter, Percina tanasi, is neither a distinct species nor a subspecies,” when the study actually doesn’t take a position on whether the snail darter is a subspecies. This isn’t a trivial error: the Times is implying that the study concludes that the snail darter shouldn’t have stopped construction of the Tellico Dam, when in fact the study goes out of its way to say the exact opposite thing.)

Dr. Ghezelayagh’s study also examines the morphological differences between snail darters and stargazing darters, and concludes, in a nutshell, that the two types of darters are a little different, but less different than Dr. Etnier thought. For example, Dr. Etnier’s measurements revealed that the modal stargazing darter had 11 anal fin rays and the modal snail darter had 12 anal fin rays, but Dr. Ghezelayagh conducts her own measurements on a larger sample set and concludes that both types of fish have a mode of 11 anal fin rays. But, according to Dr. Ghezelayagh’s measurements, the median snail darter has about 0.4 more anal fin rays than the median stargazing darter, so Dr. Etnier was not completely off base.

Why the distinction? There are lots of possibilities. Maybe the two scientists counted anal fin rays in slightly different ways. (Here’s a YouTube video walking through how anal fin ray counts can sometimes be ambiguous, there truly is everything on the Internet.) Also, Dr. Etnier examined only the Little Tennessee River snail darters, while Dr. Ghezelayagh examined other populations of subsequently-discovered snail darters. Anyway, the measurements weren’t that different—divergences of this degree are common in scientific research. I basically view Dr. Ghezelayagh as having replicated Dr. Etnier’s work.

The sturgeon in the room

Even if Dr. Etnier is a fish hero, this episode does illustrate the risk of politics influencing science.

If a scientist knows that classifying a population as a “species” will halt a construction project that the scientist opposes, then of course the scientist will have an incentive to err on the side of calling it a “species.” Or vice versa.

I’m not saying the scientist will falsify data or engage in misconduct. I’m saying that at the margins, there is no clear line between a population and a species. It’s like trying to distinguish between a dialect and a language. It’s a discretionary call. And it’s human nature for scientists to exercise their discretion to pick the side that aligns with their preferred outcome.

This can be pernicious because it can be difficult to identify bias in a scientific paper. The scientist may present the study as a neutral, objective analysis. Precisely because the scientist is an expert, the scientist may be able to conceal bias in a way that non-scientists can’t detect. Just look at Dr. Etnier’s article. Suppose that Dr. Etnier knew that the morphological differences between the stargazing darter and snail darter were much less significant than the morphological differences between other sister pairs of darters. This would have undermined his claim that the snail darter was a separate species. But how would a non-scientist know that from reading his article? The only person in a position to convey that information was the darter expert—Dr. Etnier.

Our civil litigation system deals with this problem in a rather extreme way: it prevents scientists from deciding scientific questions. Instead, when there’s a dispute over science, our system assumes scientists will act as advocates. The plaintiff and the defendant each hire expert witnesses, who are scientist/lawyer hybrids who deploy science to advocate for one side of the case. The ultimate decision is made not by an expert, but instead by a neutral judge or in some cases random citizens whose sole credential is their ignorance and hence presumed neutrality. In administrative law, however, agencies often don’t have access to dueling expert reports and instead must rely on the scientific literature as best they could.

This blog post will not try to solve the problem of bad science in administrative law. Instead, I will close with a note of optimism. My takeaway from Dr. Ghezelayagh’s article is that scientific and technological advancements have dramatically reduced the risk that “species” determinations will be influenced by bad science:

We can do now do genomic analysis, which reduces the number of borderline cases.

Genomic analysis also allows for the creation of objective criteria. “Lineages are distinct species when the genomic divergence index is greater than 0.7” is less manipulable than “Lineages are distinct species when I, a distinguished ichthyology professor, say they are.”

AI has many use cases here. For instance, AI can make scientific research more comprehensible to lay readers.

Even setting aside technological advancement, we know more stuff now than we did in 1976. Dr. Ghezelayagh was able to draw upon existing research identifying 12 sister pairs of darter species that could be used as reference pairs. That research didn’t exist in 1976.

It’s easier to identify and respond to bad science today than it was in 1976. Dr. Etnier’s original study said the snail darter was its own species because it was morphologically different from the stargazing darter. But, even based on Dr. Etnier’s data, the two types of darters weren’t that different. Why didn’t a scientist offer an opposing view to the Fish and Wildlife Service? Probably because only a minuscule number of scientists were aware of the issue. A few scientists did submit comments supporting Dr. Etnier’s position, but I’m guessing they were all people that knew Dr. Etnier. This wouldn’t happen today; the study would go viral.

Rather than lamenting the scientific errors of the past, we should exult over the present.

Amazing that a mere lawyer can figure all this out when the NYT could not. And make the presentation so interesting. This newsletter is a national asset.

I'd argue the real issue is the inability to identify part of the civil service we trust to make judgements about the *desierability* of achieving various environmental goals.

Whether or not two population groups are the same species is largely an arbitrary distinction. No sane person who was making this decision would allow whether or not you edged over the species line to decide when it's worthwhile to stop a project for conservation. Yes, they would take into account genetic diversity and weigh a host of other cost/benefits and make a judgement.

However, in the US our system makes it very difficult to meaningfully delegate judgement because a new president can just fire senior officers to get whatever outcome they want. Congress can't trust judgement of an executive agency so they instead pin the law to a kinda arbitrary science term.