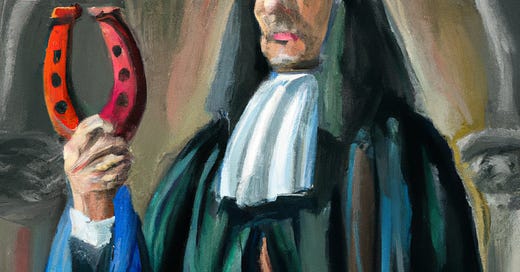

The horseshoe theory of law

How Judge Reinhardt made a comeback in the Louisiana redistricting litigation

On September 28, 2023, a divided Fifth Circuit panel issued a writ of mandamus barring a federal district court from holding a remedial hearing for purposes of drawing a new congressional map in Louisiana. The plaintiffs subsequently filed two applications to the Supreme Court seeking a stay of the Fifth Circuit’s order. Those applications remain pending, with a decision likely in the next week.

This particular shadow-docket fracas is easy to overlook. There are so many shadow-docket applications from the Fifth Circuit that it is hard to keep track of them all. (For example, DOJ has two currently-pending applications arising from the Fifth Circuit, one on ghost guns and one on communications with social media companies.) Also, the procedural history is so convoluted that it takes an effort to puzzle out what even happened.

But in my view, the Fifth Circuit’s mandamus order is sufficiently noteworthy that puzzling it out is worth the effort. Among other things, the order illustrates what I’d call the horseshoe theory of jurisprudence—the tendency of the jurisprudential approaches of very conservative judges and very progressive judges to converge.

How we got to this point

First, some background.

Based on the 2020 census, it was determined that Alabama would have seven, and Louisiana would have six, congressional districts. About 27% of Alabamans, and about 31% of Louisianans, are Black. In both states, Republican-controlled legislatures drew maps with only one majority-Black congressional district, effectively guaranteeing 6-1 and 5-1 congressional delegations in favor of Republicans, respectively.

Black voters in both states filed lawsuits against state officials, alleging that the maps violated the Voting Rights Act. In 2022, federal district courts in both states issued preliminary injunctions, finding that the plaintiffs were likely to prevail.

The Alabama court moved first. It issued its preliminary injunction on January 24, 2022. The defendants immediately appealed to the Supreme Court and sought a stay. On February 7, 2022, the Supreme Court issued a stay, ensuring that the maps drawn by the legislature would be used in the 2022 election. The Supreme Court set the Alabama case for argument in October 2022.

The Louisiana court issued its preliminary injunction on June 6, 2022. The court held that the map drawn by the legislature was illegal; the court’s order didn’t specify what map would replace it.

Legislatures, not courts, are supposed to draw maps. As such, the Supreme Court has held that when a federal court invalidates a map, it is “appropriate, whenever practicable, to afford a reasonable opportunity for the legislature to meet constitutional requirements by adopting a substitute measure rather than for the federal court to devise and order into effect its own plan.” But the court can’t force the legislature to draw a new map, and the court can’t wait forever. At some point, the court has no choice but to draw its own map (more realistically, approve a map proposed by one of the parties).

The Louisiana court wanted to have a remedial map in place by the 2022 midterm elections. Thus, the Louisiana court gave the legislature two weeks to enact a new map. It said that if the legislature didn’t act, it would impose its own map.

The Louisiana defendants immediately appealed the preliminary injunction to the Fifth Circuit. They also sought an emergency stay of the remedial hearing from the Fifth Circuit, arguing the legislature should have more than two weeks to enact a new map. On June 12, 2022, the Fifth Circuit denied the stay, holding: “the defendants do not explain, beyond bare assertion, how or why that period is too short.”

Two weeks went by and the legislature didn’t do anything. So the district court scheduled a remedial hearing for June 29, 2022.

The Louisiana state officials took their case to the Supreme Court. According to the Louisiana officials—this is a direct quote from their Supreme Court brief—the Alabama case presented “an identical issue to the one” in the Louisiana case. So—quoting that brief again—given that the Supreme Court “recently stayed a materially identical case,” the Louisiana officials argued that the Louisiana case should be stayed, too.

Seems sensible! The Supreme Court agreed. On June 28, 2022, the day before the Louisiana remedial hearing was supposed to begin, the Supreme Court granted certiorari before judgment in the Louisiana case and issued a stay. Thus, in the 2022 election, Alabama and Louisiana used the maps drawn by the state legislatures.

Conventional wisdom at the time was that the Supreme Court was going to reverse the Alabama injunction. But on June 8, 2023, after lengthy deliberation, the Supreme Court ended up affirming the Alabama injunction by a 5-4 vote, largely based on stare decisis and the clear-error standard of review.

So what to do with the Louisiana case? On June 26, 2023, the Supreme Court issued an order vacating its stay of the Louisiana injunction and dismissing the writ of certiorari as improvidently granted. The Supreme Court’s order stated: “This will allow the matter to proceed before the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit for review in the ordinary course and in advance of the 2024 congressional elections in Louisiana.”

So let’s review where we are now from the district court’s perspective:

The preliminary injunction is still in place and is now un-stayed.

The Supreme Court affirmed the Alabama preliminary injunction in a case that, according to the Louisiana state officials’ own Supreme Court brief, was “materially identical” to the Alabama case.

In 2022, the court gave the Louisiana legislature two weeks to draw a new map, and the Fifth Circuit denied a stay, reasoning that two weeks was enough.

So it seems obvious what the next step should be: hold the remedial hearing that was supposed to take place a year earlier.

It’s not clear that the district court was required, at this point, to give the Louisiana legislature additional time to enact a new map. A year earlier, the court gave the legislature two weeks, which the Fifth Circuit said was enough, and the legislature didn’t do anything. But, bending over backwards to be fair, the district court gave the legislature an additional eleven weeks to draw a new map. The remedial hearing was scheduled for October 3, 2023.

As noted above, the Supreme Court’s order un-staying the case stated that the case would “proceed before the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit for review in the ordinary course.” Consistent with that order, the Fifth Circuit scheduled oral argument on the appeal of the preliminary injunction for October 6, 2023, before the panel of Judges Elrod, Southwick, and King.

All was well.

Huh?

Until something strange happened.

On September 28, 2023, a different Fifth Circuit panel—composed of Judges Jones, Ho, and Higginson—issued a writ of mandamus halting the scheduled October 6 hearing. The panel’s vote was 2-1, with Judge Higginson dissenting.

What’s a writ of mandamus?

Well, in federal court, a litigant generally can’t appeal a district court decision until there’s a final judgment. There are some exceptions to the final judgment rule—for example, a litigant can appeal the grant or denial of a preliminary injunction. But most of the time, if you don’t like a district court’s order and the case is still going on, you have to wait until the case ends before getting appellate review. This rule makes sense—piecemeal appeals waste resources, and issues that seem important in the middle of a case often turn out to be nothingburgers by the end.

But what happens if a district judge issues some totally crazy order in a case that isn’t final? Must the litigant simply obey, no questions asked, even if the order is plainly illegal and complying with the order will cause irreparable harm?

There’s an escape hatch. A litigant can go to the court of appeals at any time and seek a so-called “writ of mandamus” seeking to overturn a district court order. But it’s extremely difficult to obtain a writ of mandamus. Among other things, the litigant must show a “clear and indisputable” right to relief. The litigant must also show that it has “no other adequate means to attain the relief he desires—a condition designed to ensure that the writ will not be used as a substitute for the regular appeals process.”

The Fifth Circuit concluded that the Louisiana state officials satisfied this stringent legal standard. In their view, it was “clear and indisputable” that the district court shouldn’t hold a remedial hearing, and the state officials had “no other adequate means” to prevent the remedial hearing from going forward.

Let’s kick the tires on this holding.

The Fifth Circuit offered two justifications for its view that the state officials’ right to relief was “clear and indisputable.” First, the Fifth Circuit observed that the district court gave the state officials only four weeks to prepare for the preliminary injunction hearing. In the Fifth Circuit’s view, this wasn’t enough preparation time, given that the plaintiffs had been “planning a lawsuit for months.”

Of course, the state officials had already appealed the preliminary injunction and sought a stay pending appeal, which was denied. Turning lemons into lemonade, the Fifth Circuit noted that the stay panel, in denying a stay, expressed some doubt about the plaintiffs’ arguments, making statements such as: “Neither the plaintiffs’ arguments nor the district court’s analysis is entirely watertight.” Therefore, concluded the Fifth Circuit, it was “clear and indisputable” that the district court shouldn’t hold a remedial hearing.

How to put this … I’m not sure this reasoning is “entirely watertight” either. One would think that for a legal proposition to be “clear and indisputable,” there should be some source of law establishing that proposition, such as a statute or judicial decision. No such source exists in this case. The stay panel’s order denying a stay does not fit the bill. The admirably restrained dissent is wry about this: “Oddly, the majority points to this court’s order denying the State’s motion for a stay pending appeal as evidence that the State has made the higher showing that it is entitled to mandamus.”

And umm … did the Louisiana state officials really have “no other adequate means” of bringing this argument to the Fifth Circuit? The Fifth Circuit thought that the defendants hadn’t gotten a fair shake at the preliminary injunction hearing. But the defendants had already appealed the preliminary injunction. Oral argument was a week away. The dissent was admirably restrained on this issue too: “There could be no more conclusive proof of the availability of appellate relief than this circumstance, where the petitioner is already an appellant pressing the same issues and seeking the same relief, challenging the same injunction in pursuance of which this hearing was scheduled.”

Also, the defendants had already sought a stay of the preliminary injunction, which was denied! This fact “clearly and indisputably” establishes that the defendants did, indeed, have another adequate means of airing their grievance to the Fifth Circuit—an excellent example of the rare situation in which the “clearly and indisputably” legal standard actually is satisfied. I find it quite interesting that the Fifth Circuit panel actually cited this stay order in support of its conclusion that mandamus relief was warranted.

(“Last Exit to Springfield,” the Simpsons episode with the “dental plan / Lisa needs braces” scene, is commonly considered to be the greatest Simpsons episode of all time. Those of you who do not get that pop culture reference, please skip to the next paragraph. Those of you who do, two points. First, because of the efforts of an anonymous YouTube hero, you can now watch “dental plan / Lisa needs braces” for ten hours. Second, if I was better with computers, I’d create a version of the scene substituting “dental plan / Lisa needs braces” with “no other adequate means / oral argument is next week.” I realize I’m the only person who would find this funny.)

The Fifth Circuit’s second justification for granting mandamus relief was its view that the district court didn’t give the state legislature enough time to enact a remedial map. As the Fifth Circuit put it, “a court must afford the legislative body that becomes liable for a Section 2 violation the first opportunity to accomplish the difficult and politically fraught task of redistricting.” Eleven weeks in 2023, plus two weeks in 2022, wasn’t enough, the Fifth Circuit thought.

This holding is also, let us say, not watertight. Let’s start with the fact that the defendants never made this argument. The state legislature, who intervened in the case and would be the appropriate litigant to make this argument, never argued in the district court that it lacked sufficient time and didn’t even seek mandamus relief. The Louisiana officials who did seek mandamus relief—Attorney General Jeff Landry and Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin—didn’t make this argument either. Instead, their mandamus petition made unrelated arguments, such as that the preliminary injunction was moot.

As noted above, the plaintiffs sought a stay of the mandamus order in the Supreme Court. The state officials’ response brief contains a telling statement:

The Plaintiffs’ argument that the legislature has not yet taken it upon itself to create a remedial map provides no support for the argument that the Fifth Circuit erred. The legislature is currently defending its enacted map via a merits appeal from the 2022 preliminary-injunction liability finding (oral argument was held in that proceeding on Friday, October 6, 2023). It makes no sense for the Louisiana legislature to effect a remedy against itself while seeking to demonstrate that the district court was wrong to conclude that the Plaintiffs’ are entitled to a remedy.

In other words, they still don’t say the legislature wasn’t given enough time to enact remedial maps. They’re saying that the legislature shouldn’t have to do anything while there are appeals pending—a completely different theory.

How does the Fifth Circuit justify reaching this conclusion sua sponte? It doesn’t. Instead, the court simply declines to disclose that it was adopting an argument that the litigants did not make.

Even if the state officials made this argument, it would be wrong. Why is it “clear and indisputable” that 11 weeks aren’t enough? There’s no statute, rule, scheduling order, judicial decision, or even Substack post saying 11 weeks aren’t enough. The closest data point is a prior stay panel order holding that 2 weeks was enough. The case cited by the Fifth Circuit on this issue, Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364, 387 (5th Cir. 1984), is completely different from this case: the district court in that case solicited comment on a court-drawn remedial map the same day the court found the violation, and didn’t hold any evidentiary hearing on the remedial map, leading to the absence of any factual record whatsoever.

What about the “no other adequate means” requirement? The Fifth Circuit suggests that the defendants had “no other adequate means” of challenging the timing of the remedial order because only the preliminary injunction—which antedated the order scheduling the remedial hearing—is on appeal. (To quote the panel majority: “Nor does the dissent explain how the panel that will hear the merits of the preliminary injunction would have jurisdiction to order relief to the state on the scheduling of the fifteen-month-later separately litigated remedy hearing”).

Yeah, but an order staying the preliminary injunction would have the effect of staying the remedial hearing. How do we know this? Because it already happened! When the Supreme Court stayed the preliminary injunction, the remedial hearing was also stayed. Also, the prior stay panel did consider (and reject) Louisiana’s argument regarding the timing of the remedial hearing.

Also, the defendants would be free to appeal the remedial order after it’s entered. Why isn’t that an adequate means of challenging the remedial order? Here’s what the panel says:

The plaintiffs respond that the state may adequately appeal following the decision formulating a court-ordered redistricting plan. That outcome would embarrass the federal judiciary and thwart rational procedures. Denying mandamus effectively means a two-track set of appeals on the merits and the court-ordered plan. No matter the outcome—or timing—of this court’s merits panel determination, one side will seek relief in the Supreme Court. Similarly, the anticipated court-ordered redistricting plan will be appealed to this court and likely to the Supreme Court. And all of this will persist well into the 2024 election year. The likelihood of conflicting courts’ scheduling and determinations will create uncertainty for the state and, more important, the candidates and electorate who may be placed into new congressional districts. In sum, while there is on paper a right to appeal whatever decision the district court renders on drawing its own redistricting maps, the paper right is a precursor to legal chaos.

I’m baffled by this. The judges say the judiciary would be “embarrassed.” Who would be embarrassed and why? What is embarrassing about an appeal?

The judges are concerned about “uncertainty.” Wouldn’t a court-ordered map, well in advance of the election, reduce uncertainty? Of course, it’s not yet clear whether the preliminary injunction will be affirmed or reversed, but that’s true with or without a remedial map. Why does knowing what the remedial map would look like increase uncertainty?

Reading between the lines, the panel seems so sure the injunction is going to be reversed that it doesn’t want the public’s minds polluted by a new map showing two majority-Black districts, even if the new map is later reversed. Is the panel aware that the Supreme Court affirmed an injunction in the Alabama case, which according to the Louisiana officials themselves, is “materially identical” to the Louisiana case?

The judges are concerned about “chaos.” How does it introduce “chaos” if appellate courts get more time to consider the legality of the new map? I thought that “chaos” happens when courts issue election-related orders too late, not too early. Perhaps the panel anticipates that if the remedial hearing is delayed, then the new map can be delayed until 2026. But the Supreme Court has already said, in this very case, that the case should be resolved prior to the 2024 election!

The lions (no longer) sleep tonight.

The Fifth Circuit’s order brings back memories.

I’ve been following federal appellate courts since I graduated from law school in 2007. To my mind, the biggest change to the judiciary since that time is the disappearance of a certain style of progressive judging that a select number of judges used to employ. Most of these judges were appointees of President Carter; notable examples were Judges Stephen Reinhardt and Harry Pregerson on the Ninth Circuit and Judge Boyce Martin on the Sixth Circuit. Obituaries of Judge Reinhardt and Judge Pregerson refer to them as “liberal lions,” so I’ll call these judges “lions” for lack of a better term.

The lions are gone. Although many Clinton and Obama appointees are quite progressive, none of them are lions in the same way as the Carter appointees. (Perhaps some Biden appointees will be lions; we’ll have to wait and see.)

What made the lions unique? Their jurisprudential style had certain hallmarks:

They ruled on grounds never argued by the parties. The lions, and Judge Reinhardt in particular, were famous for essentially substituting themselves as counsel for litigants and ruling based on arguments that the litigants did not make. United States v. Sineneng-Smith, 140 S. Ct. 1575 (2020) is a good example—after a criminal defendant briefed and argued an appeal without challenging the constitutionality of the statute of conviction, a panel that included Judge Reinhardt invited the Federal Defender Organizations of the Ninth Circuit, the Immigrant Defense Project, and the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild to submit amicus briefs on whether the statute might be unconstitutional. Lo and behold, the amici argued it was unconstitutional. The panel held reargument and (shortly after Judge Reinhardt’s passing) duly struck down the statute, only to be reversed 9-0 by the Supreme Court for improperly inserting new arguments into the case. Kennedy v. Lockyer, 379 F.3d 1041 (9th Cir. 2004), is another spectacular example of this genre.

They believed that a judge’s personal sense of justice could constitute clearly established law. Many, likely all, judges are motivated, at least in part, by their personal sense of right and wrong. The lions, however, were willing to hold that their personal sense of justice was adequate to satisfy legal standards that required the identification of clearly established law. For example, under the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, a/k/a AEDPA, federal judges are (in some cases) barred from granting habeas relief to state prisoners unless the prisoner can show that the state court engaged in an “unreasonable application of clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.” Notwithstanding this legal standard, the lions would regularly find, particularly in death penalty cases, that a state court did something they perceived as unfair, and simply proclaim without further analysis that the state court’s conclusion was an “unreasonable application of clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court” even when the Supreme Court hadn’t said anything remotely on point. Carey v. Musladin, 549 U.S. 70 (2006), one of many 9-0 reversals of Judge Reinhardt, offers a good example.

They disregarded standards of review. Related to the prior point, one hallmark of these judges’ approach was that standards of review didn’t affect outcomes. Judges are supposed to be sensitive to whether they are reviewing decisions de novo or applying some type of deferential standard (abuse-of-discretion, clear-error, substantial-evidence, and so forth). Most judges care about these distinctions, but for the lions, the standard of review did not matter; once they perceived an injustice, the wronged party would win, standard of review be damned. As an example, appeals of asylum denials are subject to a highly deferential standard of review, yet Judge Reinhardt voted to reverse asylum denials an incredible 62% of the time (Judge Pregerson’s percentage was a nearly-as-impressive 46%).

They took extraordinary measures to ensure that the “right” judges decided important cases. I wouldn’t say the judges did anything illegal or unethical to influence panel assignments, but if there was any procedural mechanism to ensure that an important case was decided by a left-leaning panel, they would use it. The Sixth Circuit proceedings in Grutter v. Bollinger, in which Judge Martin took certain controversial steps that had the effect of ensuring a 5-4 liberal majority in the en banc court (leading to heated, dueling opinions), is a case in point.

They viewed the Supreme Court as an antagonist. The lions would not out-and-out defy the Supreme Court, but if there was any conceivable path around a Supreme Court decision or order they didn’t like, they would take it. As Judge Reinhardt said about the Supreme Court, “they can’t catch ‘em all.” One famous example involved the execution of Robert Harris, in which Judge Pregerson phoned in a stay of execution after the Supreme Court had already vacated three other stays, leading the Supreme Court to ban the Ninth Circuit from issuing any stay for any reason without pre-approval by the Supreme Court.

These and other judicial tactics sometimes led the lions’ detractors to characterize them as unprincipled. But I don’t think that’s right. The lions definitely had principles—those principles simply reflected a different vision of the judicial role than the vision held by more mainstream judges. They viewed the judge’s role as advancing a particular vision of social justice, rather than using neutral principles to decide disputes. As Judge Reinhardt put it in his article entitled “The Role of Social Justice in Deciding Cases”: “The purpose of our legal system is not to provide an abstract code of rigid rules; rather it is to promote values that are compatible with the vision of a just existence for all individuals.”

The lions were regularly reversed in unanimous decisions by the Supreme Court, which led some commentators to characterize them as more liberal than even the Democratic-appointed Justices. I don’t think that’s right, either. For example, I don’t think that Judge Reinhardt had a more expansive view of a woman’s right to an abortion than, say, Justice Ginsburg. Instead, I think judges like Justice Ginsburg and judges like Judge Reinhardt differed on whether decisions should be made based on neutral principles or instead based on outcomes. To a judge like Justice Ginsburg, the question was always: “what does the law require”? She might have had progressive views of what particular laws required, but at core, she believed that a judge was supposed to apply laws neutrally and follow the law where it went. To a lion, the question was more like: “is there a way to decide this legal question in a way that will advance the substantive outcome I believe is more just?” This is how lawyers think about cases they are litigating—they try to take positions that will help them win—and the lions were essentially public-interest lawyers sitting behind the bench.

Everything old is new again.

The “horseshoe theory” of politics, a theory famous enough to have its own Wikipedia article, posits that “the far-left and the far-right, rather than being at opposite and opposing ends of a linear continuum of the political spectrum, closely resemble each other, analogous to the way that the opposite ends of a horseshoe are close together.”

I think the “horseshoe theory” applies to judging too: the jurisprudential styles of very progressive and very conservative judges tend to converge. Obviously, the conservative lions’ and liberal lions’ visions of social justice diverge, but their views of how judges should go about achieving those visions are aligned.

The Fifth Circuit’s mandamus order is a case in point. Although the judges in the panel majority are considered to be quite conservative, the panel’s mandamus order ticks every “lion” box:

Ruling sua sponte. The Fifth Circuit apparently viewed it as irrelevant that the litigants did not make the argument that the court adopted.

Believing that a judge’s personal sense of justice could constitute clearly established law. No statute or case established, much less clearly and indisputably established, that the district court erred. The judges in the majority found that standard satisfied based on little more than their deep belief that the district judge did something wrong.

Disregarding standards of review. Even outside the mandamus context, trial management decisions are reviewed for abuse of discretion. In the mandamus context, the degree of deference to such decisions is extreme. This standard of review had little effect on the court’s deliberations.

Granting a stay in a case that was already assigned to a different merits panel. This is a particularly remarkable aspect of the Fifth Circuit’s order, and it is exactly the kind of thing that Judge Reinhardt would have done in his heyday.

Viewing the Supreme Court as an antagonist. The Supreme Court affirmed the Alabama injunction and stated that the Louisiana dispute should be resolved before the 2024 election. The Fifth Circuit’s order is in some tension, to say the least, with that guidance.

Indeed, if one reverses the polarity of the litigants—say, if this was a case in which white voters sued Democratic state officials alleging that a majority-Black district was a racially discriminatory gerrymander, a type of lawsuit that was common in the lions’ heyday—it is easy to imagine Judge Reinhardt or Judge Pregerson writing a decision virtually identical to this one.

Taking a step back, the Fifth Circuit’s decision is readily understood as reflecting the exact judicial philosophy that the lions espoused—a philosophy that requires judges to decide all issues, even subsidiary procedural issues, with the primary goal of advancing their personal vision of justice. The Fifth Circuit judges clearly believe that Louisiana should be able to use the legislature-drawn maps. If one understands their decision-making algorithm to be “decide all subsidiary issues with an eye toward maximizing the probability of achieving that outcome,” everything the panel did makes perfect sense.

I’m not sure the Supreme Court will get involved in this particular row, although I imagine the Court will ensure that the plaintiffs, if they prevail, will have the benefit of a new map in the 2024 election. More generally, however, the Supreme Court has been quite willing to stay or overturn Fifth Circuit decisions, and that trend is likely to continue. I don’t think this reflects that the Fifth Circuit is “more conservative” than the Supreme Court, just as Judge Reinhardt wasn’t “more liberal” than Justice Ginsburg. Instead, it reflects disagreement over whether to view the “Rule of Law as a Law of Rules,” as Justice Scalia famously put it, or whether judicial decision-making should be oriented towards implementing judges’ substantive vision of social justice.

It would seem that the "horseshoe theory" also applies to the 5th Circuit's decision in the mifepristone case. It's probably even more applicable to Judge Kacsmaryk's decision In that, and in other cases). And Judge Reinhard's observation/hope that "they can't catch them all" certainly applies as well.

Supremely good article. The lions seem to want a government of men.