Sometimes, the Supreme Court issues decisions holding that federal criminal statutes are narrower than lower courts previously thought.

For example, a federal law imposes criminal liability on anyone who “intentionally accesses a computer without authorization or exceeds authorized access.” Before 2021, several lower courts held that this law covers defendants who access information that they’re allowed to access, but do so for improper reasons. In Van Buren v. United States, 141 S. Ct. 1648 (2021), the Supreme Court took a narrower view of the law. It held that the law “covers those who obtain information from particular areas in the computer—such as files, folders, or databases—to which their computer access does not extend.” But it does not cover those who “have improper motives for obtaining information that is otherwise available to them.”

As another example, it is a federal crime for certain classes of persons (felons, unlawful aliens, drug users, etc.) to possess a firearm. Sometimes, people don’t know that they fall within one of these classes. For many years, lower courts held that this wasn’t a defense to criminal liability. As long as the defendant knew he was possessing the firearm, he could be convicted, regardless of whether he knew he wasn’t allowed to possess it. In Rehaif v. United States, 139 S. Ct. 2191 (2019), the Supreme Court rejected those lower-court decisions. It held that a defendant could be convicted only if he knew he couldn’t possess the firearm.

When the Supreme Court holds that a federal criminal statute is narrower than lower courts previously thought, what happens to prisoners who were previously convicted under lower courts’ inappropriately broad interpretations? The Supreme Court’s new decision establishes that they didn’t break the law. In other words, they’re innocent. Can they get out of prison?

On June 22, 2023, in Jones v. Hendrix, the Supreme Court held that in some cases, the answer is no. In a 6-3 decision by Justice Thomas, the Court concluded that if a federal prisoner has previously filed a post-conviction challenge—even addressing a completely unrelated issue—the prisoner is out of luck. The prisoner cannot file a second post-conviction challenge arguing that, under the Supreme Court’s new decision, his actions weren’t a crime. Even if the federal prisoner is indisputably innocent, the prisoner must serve his full sentence.

Jones’s holding seems pretty ghoulish. But Justice Thomas’s majority opinion is well-written and persuasive. He puts forward a powerful argument that under the plain text of the applicable federal statutes, federal prisoners are forbidden from bringing this type of challenge.

Justice Jackson’s dissent is also well-written and persuasive. She puts forward a powerful argument that the majority’s interpretation conflicts with congressional intent and would lead to unfair consequences. In the end, Jones presents a tough, close issue.

The purpose of this post is not to defend one side or the other of Jones. It’s to advocate a statutory fix that would allow federal prisoners to file successive Section 2255 petitions when new Supreme Court decisions establish their innocence.

This is not a tough, close issue. It is an obviously correct position that should prevail by unanimous voice votes in the House and Senate.

It is obviously correct because:

It is bad that innocent people are in prison.

The rules governing which prisoners can and can’t bring post-conviction challenges are arbitrary, random, and nonsensical.

We are in this situation because Congress made an accidental drafting error, which should be fixed.

I understand that Democrats are generally more likely to favor reforms that assist prisoners than Republicans. But in this case, the proposed reform—which fixes an irrational system and benefits the minuscule fraction of prisoners who can prove their innocence—should be equally appealing to both sides of the aisle.

I know some readers of this Substack work on the Hill or in Hill-adjacent positions. Whether you are a Republican or a Democrat, I urge you to do whatever it takes to fix Section 2255 as quickly as possible. Let’s make the world a better place.

(Dall-E also wants justice.)

I didn’t do it!

When a person is convicted of a federal crime, he has the right to appeal to a federal appellate court, and then the U.S. Supreme Court. That process is called “direct review.” When direct review is over, the conviction becomes final.

Sometimes, prisoners seek to overturn their convictions after the convictions have become final. In legal lingo, this is called a “collateral challenge.” For example, a prisoner might allege that he received ineffective assistance of counsel during the direct review process, or that the prosecutor unlawfully withheld exculpatory evidence.

Or—relevant to this post—the prisoner might allege that there is new information establishing that he didn’t commit a crime. This can mean one of three things:

1. New evidence shows that he didn’t do what the prosecutor claims he did.

2. A new decision shows that his actions didn’t violate the law.

3. A new decision shows that the law that he violated is unconstitutional.

Let’s call those theories Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3.

There’s a federal statute, 28 U.S.C. § 2255, that allows federal prisoners to bring collateral challenges to their convictions. Ordinarily, such challenges must be filed within one year of the date the conviction became final. But what happens if the new information establishing that the prisoner didn’t commit a crime comes out after the one-year clock expires?

It depends on whether the prisoner has previously filed a Section 2255 challenge.

If a prisoner hasn’t previously filed a Section 2255 challenge, the prisoner can file such a challenge in all three types of innocence cases, even if more than a year has passed since his conviction. The one-year clock restarts on “the date on which the facts supporting the claim or claims presented could have been discovered through the exercise of due diligence”—which covers Type 1 cases—and “the date on which the right asserted was initially recognized by the Supreme Court, if that right has been newly recognized by the Supreme Court and made retroactively applicable to cases on collateral review”—which covers Type 2 and Type 3 cases.

If a prisoner has previously filed a Section 2255 motion, the prisoner can file a successive Section 2255 motion in Type 1 cases and Type 3 cases, but not Type 2 cases. That is, a prisoner can file a successive Section 2255 motion if he can show “newly discovered evidence that, if proven and viewed in light of the evidence as a whole, would be sufficient to establish by clear and convincing evidence that no reasonable factfinder would have found the movant guilty of the offense”—i.e., Type 1 cases—or “a new rule of constitutional law, made retroactive to cases on collateral review by the Supreme Court, that was previously unavailable.”—i.e., Type 3 cases. But he can’t file a successive Section 2255 motion based on a new statutory-interpretation decision—i.e., Type 2 cases. This rule applies even if he filed the previous Section 2255 motion on a completely unrelated issue, such as, say, an allegation of ineffective assistance of counsel during sentencing.

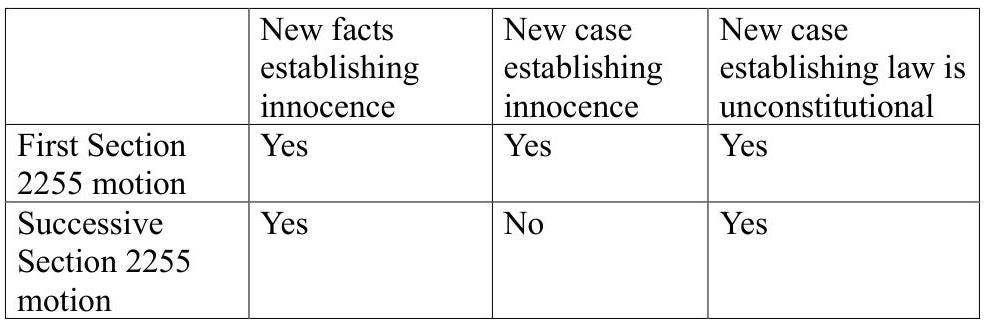

So here’s a grid of what arguments prisoners can and can’t make under Section 2255:

A primer on Jones

The question in Jones was, what happens to prisoners in the “No” box?

In 2000, Jones was convicted of being a felon in possession of a firearm. After his conviction, he filed a Section 2255 motion challenging his sentence. He obtained partial relief—a vacatur of one of his concurrent sentences. But his conviction stayed intact, so he stayed in prison.

Nineteen years after his conviction, the Supreme Court decided Rehaif, which, as explained above, holds that the felon-in-possession statute requires that the felon knew he couldn’t possess a gun. At the time of Jones’s conviction, circuit precedent established that lack of knowledge wasn’t a defense, but Rehaif overturned that circuit precedent. Jones argued that he didn’t know that he couldn’t possess a gun, so he was innocent under Rehaif.

The problem for Jones was that he had already filed a Section 2255 motion. Thus, he fell in that “No” box.

Jones argued that although he lacked a remedy under Section 2255, he could bring a habeas corpus claim under a different statute, Section 2241. Jones relied on Section 2255’s so-called “savings clause,” which permits a prisoner to bring a Section 2241 claim when Section 2255 is “inadequate or ineffective to test the legality of his detention.” Most lower courts had accepted this argument, but in Jones, the Supreme Court rejected it by a 6-3 vote. It held that the savings clause does not apply in this situation. For prisoners seeking to overturn their convictions on the ground that a new statutory-interpretation decision establishes their innocence, it’s Section 2255 or bust. And so, prisoners in the “No” box have no remedy at all.

Justice Jackson dissented, agreeing with Jones’s interpretation of the savings clause. Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan filed a short, separate dissent endorsing the government’s interpretation of the savings clause, which was narrower than Jones’s interpretation but still would have allowed prisoners to seek relief under Section 2241 in certain actual-innocence cases.

The majority and Justice Jackson battle toe-to-toe as to this intricate issue of statutory interpretation. I am not going to relitigate these opinions here. Both are well written and one could reasonably agree with either of them. Six is greater than three, so from now on, unless Congress amends Section 2255, prisoners in the “No” box must stay in prison, even if a new decision incontrovertibly establishes their innocence.

Down with madness

Congress should amend Section 2255 immediately. It makes no sense to have that lower middle box be a “no” when all the boxes around it are “yes.” Whether you’re a finality-loving Republican or a habeas-loving Democrat, this scheme is madness.

Let’s start with the elephant in the room. It’s bad for innocent people to be in prison. Even if you support being tough on crime, you should not support being tough on non-crime.

Incarcerating an innocent inmate is grossly unfair to the inmate, obviously. It’s harmful for taxpayers, who must fund the innocent inmate’s incarceration. It also corrodes respect for the criminal justice system. I can’t think of a better way to undermine the justice system’s legitimacy than to intentionally incarcerate innocent people, especially when those people are behind bars because the judge incorrectly interpreted a law.

(I’d also support changing Section 2255 to benefit prisoners who can show, based on Supreme Court statutory-interpretation decisions, that they are serving sentences exceeding the statutory maximum for their crimes. For example, if a prisoner’s sentence is enhanced based on the Armed Career Criminal Act, and a subsequent Supreme Court case narrows the scope of the Armed Career Criminal Act, as not infrequently occurs, I’d support allowing a prisoner to bring a successive Section 2255 claim. Such prisoners are less sympathetic than innocent prisoners, but it’s still bad for prisoners to be serving illegal sentences. But given that this post is already too long, I’ll focus on the goal of vindicating prisoners who are innocent of their crimes.)

Finality is important too. One can’t always assume that additional litigation yields better outcomes. Permitting prisoners to reopen decades-old convictions reopens old wounds and can be unfair to the prosecution. I get that.

My problem with the status quo isn’t just that some innocent people are behind bars. My problem is that the line between which prisoners can and can’t challenge their convictions makes absolutely no sense.

Steel-manning the contrary argument, I can think of three reasons why one might want to bar prisoners from bringing successive Section 2255 claims asserting their innocence:

You should only get one shot to file a collateral attack overturning your conviction. Finality is good. At some point, enough is enough.

Permitting collateral attacks years after the conviction will result in guilty people going free.

Our courts are clogged; permitting such successive attacks will yield a haystack of litigation that can’t be justified based on the occasional needle.

As I explain below, although these arguments may be meritorious in the abstract, none of them can justify our current irrational system.

Enough isn’t enough

Before 1996, prisoners had (relatively) free rein to file successive habeas petitions. Some prisoners abused this privilege, filing challenges over and over with new theories as to why they should be released. In 1996, Congress sharply limited successive Section 2255 petitions by permitting them only in Type 1 cases (new facts) and Type 3 cases (new constitutional decisions).

In general, limiting successive habeas petitions makes sense. We want to give prisoners the incentive to present all their arguments in a single petition, rather than letting them challenge their convictions over and over and over again.

But this reasoning doesn’t apply to prisoners who have no idea that a future decision might come down that might benefit them. Look at Jones’s case. He was convicted in 2000. He had a one-year deadline to file a Section 2255 petition. He met that deadline, and partially prevailed. He didn’t intentionally, or even accidentally, omit an argument in his petition. Rather, the argument wasn’t available to him until the Supreme Court decided an issue in his favor 19 years later. Why punish him for filing a successful Section 2255 petition that omitted an argument he could not even theoretically have made?

Congress partially recognized this point. That’s why it allowed successive Section 2255 challenges based on new facts establishing innocence and new constitutional decisions. There is no rational justification for barring such challenges based on new decisions establishing innocence.

Let’s start by comparing Type 1 claims (new facts establishing innocence) with Type 2 claims (new law establishing innocence). I have no idea why we’d permit people to bring successive petitions establishing innocence based on new facts, but not new law. Innocence is innocence; why is one type of innocence better than the other?

In fact, it should go the other way. One concern about permitting successive petitions based on new evidence is that there’s often reason to be skeptical of claims of new evidence, especially many years after a conviction. Is it really reliable? Did the prisoner really lack a fair shot to raise this evidence earlier? By contrast, when a new Supreme Court decision comes out, we can be 100% certain the decision is reliable and 100% certain that the prisoner couldn’t invoke the decision before the decision was released. What sense does it make to permit the first category of claims but not the second?

But let’s say you disagree with this analysis and believe there is something special about new facts that justifies successive habeas petitions, that doesn’t apply to new law. If you hold that view, the scheme is still nonsensical because you actually can rely on new law—but it has to be new constitutional rather than statutory law.

As noted above, a prisoner can file successive Section 2255 challenges based on retroactive constitutional decisions. Retroactivity is a complicated topic, but generally speaking, decisions are retroactive when they are “substantive” rather than “procedural”—that is, when they govern what can and cannot be punished, rather than what procedural protections are available to the accused. Thus, decisions interpreting the scope of criminal statutes are generally retroactive. An example of a retroactive constitutional decision would be a decision striking down a statute on First Amendment grounds. Cases like United States v. Alvarez, 567 U.S. 709 (2012), which struck down a federal ban on lying about winning the Medal of Honor, and United States v. Stevens, 559 U.S. 460 (2009), which struck down a federal ban on distributing depictions of animal abuse, would likely qualify as retroactive constitutional decisions. A decision holding that a criminal statute exceeds Congress’s Commerce Clause authority, such as United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995), would also likely qualify as retroactive.

In other words, if you’re relying on a decision holding you can’t be punished for violating a statute because the statute is unconstitutional, you can file a successive habeas petition. But if you’re relying on a decision holding that you can’t be punished for violating a statute because you didn’t violate it, you can’t.

This distinction implies that it is somehow more unjust to incarcerate a person who is guilty of an unconstitutional law than to incarcerate a person who is innocent of a constitutional law. Why, though? If you’re innocent, how does it at all mitigate the injustice that the law, if applied to guilty people, is constitutional? If someone is in prison for a murder he didn’t commit, should we really say “well, this isn’t that unjust because if the prisoner, hypothetically, were guilty of murder, the law against murder wouldn’t be unconstitutional”?

Moreover, the Supreme Court sometimes says that it doesn’t even need to reach a First Amendment challenge to a statute because the statute—correctly construed—doesn’t cover the defendant’s conduct. For example, in Elonis v. United States, 575 U.S. 723 (2015), the defendant was convicted of violating a federal statute banning threatening communications, even though the jury wasn’t asked to find whether he intended—or was even reckless—as to whether his communications would be perceived as threatening. Elonis challenged his conviction under the First Amendment, but the Supreme Court held that it didn’t need to address the First Amendment issue because Congress didn’t intend to criminalize threatening communications when the defendant was merely negligent as to how his communication would be perceived. Because this was a statutory-interpretation decision, prisoners can’t file successive Section 2255 petitions based on it. But if Congress had criminalized Elonis’s behavior, the statute would have been held unconstitutional under the First Amendment, as the Supreme Court held this past week in Counterman v. Colorado. This would have meant that prisoners could have filed successive Section 2255 petitions. In other words, if Congress didn’t want to ban the prisoner’s conduct, the prisoner is worse off than if Congress did want to ban the conduct. Why would this be?

Or, to take another example, because Congress did want to ban animal torture videos and lying about winning the Medal of Honor, the Supreme Court had no choice but to reach First Amendment challenges to those statutes—and it struck them down, opening the door for prisoners convicted under those statutes to bring successive Section 2255 challenges. In other words, prisoners that Congress wanted to punish are given special rights that are denied to prisoners that Congress didn’t want to punish. Why?

Circling back to the original point, it makes sense that Congress would generally limit the filing of successive habeas petitions. The problem is that banning the filing of successive habeas petitions based on new law showing innocence—while permitting them based on new facts showing innocence and new law showing the law’s unconstitutionality—makes no sense.

Let the innocent people out, keep the guilty people in

Another argument against permitting innocent people to bring successive challenges is that they aren’t always innocent.

Suppose the Supreme Court releases a decision construing a criminal statute more narrowly than lower courts previously did. A prisoner might allege he is innocent under the narrower interpretation. But prisoners allege a lot of things, and for all we know, he might have been convicted under any interpretation. Years after the conviction, however, it might not be possible to prove that—witnesses may be dead, evidence may be lost. It would be bad, in that situation, for the guilty prisoner to be released.

Jones’s case illustrates this problem. Nineteen years after his conviction, he alleges he didn’t know he wasn’t allowed to possess the firearm because he thought his felony convictions had been expunged. Well … that may or may not be true. Actually, the government says it isn’t true given that Jones had 11 prior felony convictions and admitted to the police that he shouldn’t have a gun. It’s unfair to the government to have to litigate this issue 19 years later.

This argument doesn’t justify leaving the status quo intact.

First, one can take care of this problem by requiring the defendant to prove his innocence. There’s already a legal standard in place for defendants attempting to prove their innocence in post-conviction challenges. The defendant bears the burden of proving that no reasonable juror would have convicted him, and the government may rebut this argument based on any evidence (not just evidence admitted at the trial). So Jones probably would have lost, and only a narrow slice of prisoners go free. In Jones, the Justice Department argued that this legal standard was sufficiently stringent to filter out guilty prisoners. Why should we disbelieve it?

Second, and crucially, the identical concern exists for prisoners who haven’t filed a previous Section 2255 challenge, yet those prisoners are permitted to file Section 2255 challenges based on statutory-interpretation decisions. As Justice Jackson’s dissent notes, “Under the Court’s interpretation, a prisoner whose conviction became final 30 years ago can assert a Rehaif claim if he never previously filed a §2255 motion, whereas someone whose conviction became final 2 years ago cannot if he has already had a §2255 petition adjudicated.” Obviously we want some way of filtering out guilty prisoners, but a prisoner’s decision to file an unrelated Section 2255 petition years earlier has no relevance whatsoever to whether permitting the new petition will allow a guilty inmate to go free.

Concern over freeing guilty prisoners justifies a rule limiting post-conviction petitions, but it doesn’t justify the current rule.

Fix the air conditioning

One frequent justification for limiting post-conviction challenges, especially successive post-conviction challenges, is that the overwhelming majority of them are meritless, and one shouldn’t permit them based on the occasional needle in the haystack. This is often a good argument, but in this case it’s a bad argument.

First, most lower courts have permitted such claims (via Section 2241) for years. There hasn’t been a flood of litigation, and there’s no reason that fixing Section 2255 would create such a flood.

Second, prisoners can file statutory-innocence claims only if there’s a new statutory decision covering their statute of conviction. That doesn’t happen very often—maybe once or twice a year—so the cohort of potentially affected prisoners is inherently small.

Third, in 2018, the Republican-controlled Congress enacted and President Trump signed the First Step Act, which, among other things, permitted thousands of prisoners convicted of crack cocaine offenses to be resentenced. If you’re a Republican who voted for the First Step Act (which I strongly support), it makes no sense to oppose a Section 2255 fix on the ground that it creates too much litigation. If you’re going to enact a statute opening new resentencing opportunities for thousands of guilty prisoners with lawful sentences, why would you oppose fixing a law that bars a tiny group of innocent prisoners from vindicating their rights, especially when similarly situated prisoners have already enjoyed those rights under years of lower-court precedent? It’s like spending millions of dollars on artwork for a building interior, and then, after the air conditioning breaks, refusing to fix it because it’s too expensive.

Why did Congress bar these claims?

What makes the status quo even more galling is that the current statute almost certainly reflects an accidental drafting error.

Justice Jackson’s dissent explains this in detail (on pages 20-21). In a nutshell, the limitations on second and successive Section 2255 petition was enacted in 1996 as part of the (in)famous Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. Congress altered the rules governing successive challenges for federal prisoners at the same time as it altered the rules for state prisoners. For state prisoners, the only Supreme Court decisions that would justify successive habeas petitions are constitutional decisions, because the Supreme Court doesn’t interpret state statutes. So, Congress said that a state prisoner can file a successive habeas petition based on new, retroactive constitutional decisions. And Congress copied that language into Section 2255, accidentally omitting any reference to statutory-interpretation decisions.

So, depressingly, innocent federal prisoners have to stay in jail because of two mistakes. They were wrongfully convicted in the first place because their judges made a mistake. And they can’t get relief from those mistakes because Congress made a different mistake.

Why hasn’t Congress fixed this mistake for the past 25+ years? It didn’t have to, because most lower courts were allowing such claims to proceed via Section 2241. After Jones, that door is closed. Now is the time to fix it.

***

I understand that if you’re a Republican, overturning a decision by the Court’s six Republican appointees is a tough sell. But the Court didn’t say that the current regime makes sense.

Judges on both sides of the philosophical spectrum routinely insist that they are interpreting the law as written rather than embedding their policy preferences into the law. One can debate all day whether this is always, or even sometimes, true. But in this case, it’s true! You should believe them! There is not the slightest indication in the majority decision that the Court agrees, as a policy matter, with what it construed the statute to require. It simply held that Section 2255, as currently drafted, forecloses relief, and any fix would have to come from Congress.

It is extremely rare that Congress has the opportunity to enact a reform that would so clearly improve the justice system, at so little cost. That opportunity now exists. Fix Section 2255.

In my next post, I will address 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis.

I fail to see how Jones is "a tough close issue". As you spend the rest of the essay arguing, a prisoner in Jones' situation should have access to a hearing to establish their innocence and secure their freedom. Jones is factually innocent; any statute which purports to bar the courtroom door violates due process. I read Thomas's argument, which makes a statutory case that is not necessarily wrong, but which is irrelevant in the face of the result: manifest injustice.

The government may dispute Jones' knowledge of his status, but they are required to prove that beyond a reasonable doubt.

As you point out, Congress could and should address this easily, but I will also point out that the President has a role to play. This is a case for the broad use of the pardon power to expeditiously correct the invalid conviction of many, many people.